Made in the Netherlands.

It’s a philosophy which underpins Tacx, the indoor trainer manufacturer based in Wassenaar, a suburb of Amsterdam.

“We do everything here,” says Sven Roggeveen of Tacx, our host for a tour of the Dutch firm’s factory. “That’s the philosophy of Tacx.” The company is something of a rare breed, manufacturing the majority of its products in-house against competition which outsources production to the Far East.

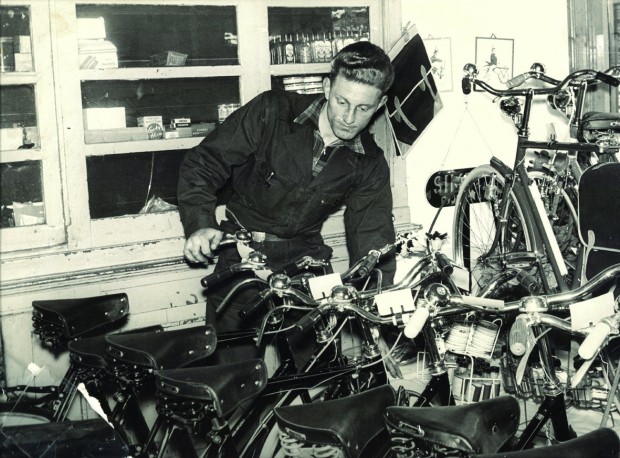

Tacx began life as a bike shop, founded by Koos Tacx in 1957, who 15 years later in 1972 started manufacturing rollers. The small retailer has grown into a company of 96 employees and one of the world’s leading manufacturers of turbo trainers and rollers, with a range which also extends to water bottles, workstands and tools.

The company moved to its current site in 1989, and the premises has grown considerably since to 9,500 square metres, but It’s still a family firm at heart. Koos, now 78, continues to arrive at work at 7am every day. His sons, Peter and Koos, run day-to-day operations, while Simon, a third generation member of the Tacx family, has also joined the firm.

Innovation runs through the veins at Tacx, says Roggeveen, and our tour gives us a sneak peek at one “top secret” product currently in development. The fact Tacx develop their range in-house from start to finish – from product design to the manufacture of moulds to assembly – allows them to stay at the forefront of the market, he says.

“When you want to develop something and you want to have it on the market as soon as possible, it’s important to have everything in-house because you can develop and manufacture products very quickly,” says Roggeveen.

“A normal company may design their products in-house but they’re made in the Far East and the process takes around two years – but we can do it in one year.”

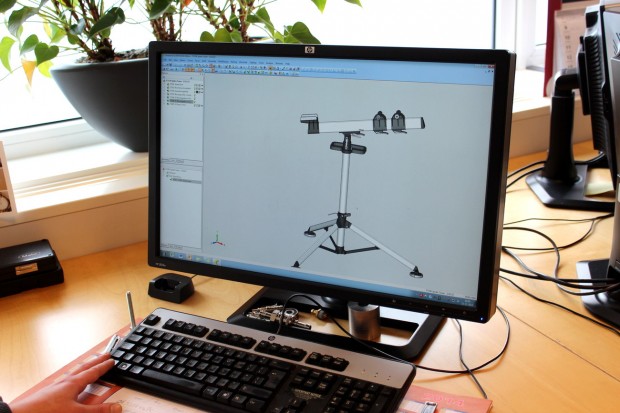

Our factory tour takes us through the four main stages of the design and manufacturing process. A new product starts with a design on a drawing board and prototypes are made using 3D printing. Moulds are then made and production begins. Steel parts are welded by robots, plastic parts are made by injection moulding machines, and an assembly line puts it all together.

“That’s what I love about working here,” says Ramon van der Stel, one of two product designers at Tacx. “At most factories you only see the end product, but here you see everything, from manufacturing the mould to the finished product.”

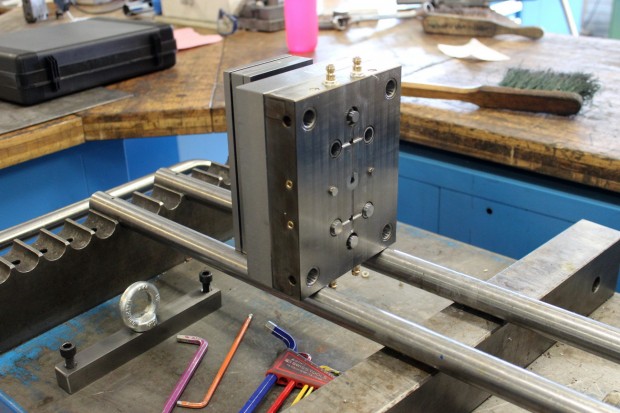

Van der Stel’s role is primarily based around the design of moulds, which form the basis of the manufacturing process for the plastic parts out of which most of Tacx’s products are formed. Each mould is a hollowed-out block of metal filled with a liquid or pliable material like plastic, glass or metal, which in turn becomes a single part – a roller drum or water bottle cap, for example – of a product.

Many manufacturers have their moulds made by a third party, but all those used by Tacx are manufacturered in-house. It’s an expensive process and one mould can cost up to 80,000 euros. The design process, therefore, must be flawless before a mould is put in to production and Tacx have used 3D printing, a layered manufacturing process which allows the production of a three-dimensional object from a digital model, for the past five years to make a prototype of each product.

“We only have one chance to get the mould right,” says van der Stel. “3D printing is a cost efficient process.”

He shows us a model of Tacx’s new iPad stand 3D-printed from nylon. The stand allows users to attach their tablet to the turbo trainer in order to have Tacx’s app software and training videos at their fingertips.

3D printing is a fast-developing technology heralded by some as a future of manufacturing and I ask van der Stel if he thinks one day consumers will be able to 3D print their own turbo trainer.

“I think so, maybe one day” he says. “It’s growing so fast. At the moment you see people 3D printing their own chess pieces and for 500 euros you can have your own 3D printer at home. Ok, it’s not using high-grade materials like those we need for a turbo trainer, which also has a large number of moving parts, but it will develop.”

Not every product is a success story, he says, and the biggest gamble is whether a consumer ultimately buys a product. “We’ve had bottle cages that have flopped, and they haven’t sold well, but we’ve spent 200,000 euros on moulds. That’s the risk you take but over the years we’ve developed an understanding of what the consumer wants.”

A mould starts as solid blocks of steel, which then have the appropriate material cut out by one of three machines. Simple shapes are cut out by a traditional milling machine, while more complex patterns are cut by a di-electrode machine, which uses electricity to remove metal at an accuracy of 1/100th of a millimetre, and a wire-cutting machine, which is more accurate still at 1/1,000th of a millimetre. One mould might use all three machines and take four weeks to make, and each part of a single mould is put together, measured, checked and double checked by one of four employees who work in this part of the factory.

How many moulds do Tacx make in a year? “Ohhhh I don’t know,” says van der Stel, “but it’s a lot. A Bushido turbo trainer, for example, needs 50 moulds.”

Once a mould is finished it’s moved to the next hall in the factory and that part is put into production. The cavernous factory floor is alive with noise: the whirr of machines, the whizz of robots, the hiss of hydraulics and the buzz as sparks fly from a welding gun.

Tacx are best known for turbo trainers but, in terms of volume, more water bottles are made in the factory than anything else. A plastic injection moulding machine making 361 water bottles an hour, its maximum rate, is the first machine we come to. A mould clamps around a tube of hot, soft plastic, which is pressed into shape and immediately cooled. The mould is released and a water bottle is revealed. Excess plastic is cut from the top (all plastic waste is recycled) and the bottle moves along a conveyor belt to the next stage of the manufacturing process. Later we see a similar machine producing caps for Lotto-Belisol bottles – one of seven WorldTour teams sponsored by Tacx – and another which screws the caps on to the bottles.

Two machines, working from six o’ clock in the morning until 11 o’ clock at night, seven days a week, produce four million bottles a year, according to Marcel de Bode, manager of the factory floor. The machines can also run overnight and be monitored by computer if demand requires, though Tacx have purchased a third machine to increase capacity. When we visit the machines are producing white 500ml bottles, though the mould can be changed if a different size or shape bottle is put into production. The same mould can be used to produce different colour bottles, though it and the machine must be cleaned and completely free of residue before the colour of the plastic is switched and production starts again in order to avoid contamination.

The factory floor has ten plastic moulding machines besides the two producing water bottles. They run 24/7 and, when we visit, one is making the drum on which the tyre sits on a turbo trainer, and another Tacx’s blue Galaxia rollers.

Robots are used to pick the part from the open mould once the injection moulding procces is complete. The mould then shuts, is filled with plastic, cooled and opened before the robot arm returns to remove the part in a process which takes a matter of seconds. Tacx have been using robots since 1979 and they now have 20 Kawasaki robots throughout the factory. As a result, much of the manufacturing process, besides the installation of the mould required for a particular part and the computation of the machines, is automated.

Each machine can make a number of parts, though the bigger the part, the more pressure required, and the bigger the machine. A small machine makes small parts, and a big machine makes big parts. The Galaxia rollers are among the biggest plastic parts Tacx produce and the machine required can generate between 280 and 1,450 tons of pressure.

“The rollers are one of the most difficult parts we make,” says de Bode. “Normally it’s difficult to create a large but thin plastic tube with a completely even surface so the mould takes longer to develop and the roller needs more cooling time before it’s released from the mould.”

Only a handful of employees roam a factory floor otherwise dominated by machines, but humans and robots work in tandem when it comes to welding the steel turbo trainer frames. On one side a Tacx employee assembles the frame in a jig while a robot welds another on the other side. The two then swap positions, the employee checks and removes the welded frame and the robot welds the frame in the jig, and thus the process continues. Continuing the Made in the Netherlands philosophy, Tacx source the steel for their turbo frames and the plastic for injection moulding from Dutch companies.

We then move into the production hall, where each product is assembled, and Fred van der Veer takes over as our guide. “I’m responsible if anything goes missing,” says van der Veer, who has been a member of the Tacx ‘family’ since 1985. “This is where everything is put together and every day, every hour, the products we are assembling could be different. This morning we were making the Satori trainer and now we’re making the Bushido.”

Everything we have seen so far comes together under his watchful eye. Bottle tops are screwed on by machine (up to 45,000 a day, says van der Veer), turbo trainers and rollers put together by employees on an assembly line and tested, and all products boxed up and shipped to distributors, retailers and customers around the world.

Some four million bottles, 100,000 indoor trainers, 50,000 tools and 40,000 workstands are made in the Tacx factory every year. It’s a vast operation which combines Dutch design with 21st Century manufacturing processes.

What started as a small local bike shop and manufacturer of rollers has developed into a worldwide brand – but Tacx’s core principle remains the same: Made in the Netherlands.

See more photos from the factory floor in our full-screen gallery.