Cycling’s relationship with the human body is like a jigsaw. It starts as hundreds of tiny pieces and slowly but surely, as a rider gets stronger and faster, each piece joins together.

That’s the thinking behind the Wilier Performance Progress Lab, which offers scientific testing to create a bespoke training plan for cyclists. Almost every cyclist has a goal they want to achieve through the sport, whether that’s losing weight, riding 100 miles, tackling a mountainous European sportive or winning races, and Wilier PPL founder Peter Webster says his programme is designed to make those goals more attainable.

“Everything about your lifestyle has an impact on your performance,” says Webster. The firm’s philosophy reflects that, he says, and Wilier PPL offer a ‘menu’ of tests which riders can pick and choose from in order to build a picture of their body.

I’m the guinea pig and have come to Rock and Road, an independent bike shop in St. Albans, to sample the menu. Rock and Road is one of 135 Wilier dealers signed up to the Performance Progress Lab, though riders needn’t be a Wilier owner to take part. Each shop becomes a lab in itself when Webster and his team arrive for a client’s session. A Wattbike and turbo trainer dominate the shop floor when I walk in.

Wilier PPL’s menu includes ‘baseline health tests’, ‘performance fitness analysis’ and ‘cycling-specific performance tests’. Riders can sign-up for individual tests or, like me, all three in order to build-up the complete picture Webster says provides the blueprint for the subsequent training plan. A lactate threshold test performed on a Wattbike is the most important piece in the jigsaw, and the final and most painful test. Webster says Wilier PPL use lactate threshold, rather than VO2 Max, as it provides the rider with “more useable data.”

I’m the guinea pig and have come to Rock and Road in St. Albans to sample the Wilier Performance Progress Lab ‘menu’

“A V02 Max test will give a result that identifies how much oxygenated blood is transported to the working muscles,” says Webster. “A lactate threshold analysis session identifies an optimum performance line, from which it is possible to understand your optimum power and heart rate.”

Key to Wilier PPL, according to Webster, is the on-going contact between his team and the rider once the tests have been completed. Each rider is issued with a comprehensive test report and a training plan is built in order to address weaknesses, build on strengths and work towards the rider’s goal. Wilier PPL charge a set fee for testing and future coaching is at an hourly rate.

Performance testing and coaching is not for everyone, concedes Webster, but neither is it the preserve of professional riders.

“A set of £1,000 wheels looks great but is it going to make you much faster?” says Webster. “And where do you go from there? There are a lot of people who have bought into the idea of heart rate but don’t actually understand the data and how it affects them.

“A sportive rider might spend £1,500 to £2,000 on a bike but their time on the bike is quite constrained, so they need to make sure they get as much as they can out of each session if they have a big goal they want to achieve.

“What we do is give you a programme to follow after the test, with the view of coming back every quarter to re-test to see where we’re at. If we predicted you’d be here and you’re not, then why not? Let’s look at what else has affected that. For example, you might be putting more hours in on the bike, but that might have affected your flexibility and power, so we’d have to redirect your training plan to cope with that.

“The point is that it’s ongoing contact. I don’t want to just test people and walk off, because there’s no point. No-one benefits from that.”

“A set of £1,000 wheels looks great but is it going to make you much faster?,” says Webster.

My session starts with a questionnaire which, owing to the forthcoming lactate threshold test, includes the usual health disclaimers, but also a lifestyle assessment (how active I am at work, perceived stress, eating habits, alcohol unit drunk per week and whether I am a smoker) and an overview of my cycling as it stands (time on the bike, riding style, what type of cyclist am I, what bike and pedals I use). We then discuss my goals – to have a decent crack at racing in 2014 – and how the subsequent tests will help form the training plan which comes as an end product.

“We’re going to break down your genetic map and what you were born to do, your lifestyle and how that’s had an impact on you, and provide a snapshot of where you are now in terms of performance,” says Webster.

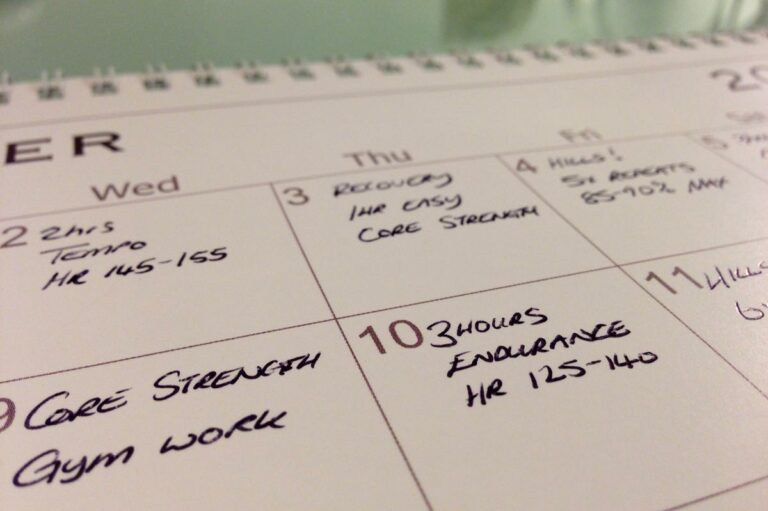

“If you’re a sportive rider who just wants to get through 100 miles then their plan will be tailored to that goal. If you have lofty ambitions in racing then your plan will reflect that. Some people really like a regimented programme which dictates exactly when they should ride, to what heart rate and power, and what they should eat, while others need to have more flexibility built in and want to have a rough idea of what they should be doing on a week-to-week basis to progress.”

The testing process is comprehensive. I change into my cycling kit and the process starts at the most basic level, with my weight and height recorded (it turns out I’m one centimetre shorter than I thought), and moves on to body composition with a series of tests which include a measurement of body fat percentage.

“If we can help somebody lose a couple of kilogrammes then straight away that’s going to help,” says Webster, “but it’s also about knowing how much someone can realistically lose and knowing the body composition helps us achieve that.”

Muscular skeletal mobility tests assess flexibility, posture and the effects of past injury or genetic adaptation. I am asked to go through a range of movements and stretches, both off the bike and with my current steed rigged up on a turbo trainer, to test my flexibility. “We try not to go down the bike fit point of view but we try and look at how your body works with the bike,” says Webster.

I admit to a genetic condition called bi-partite patella, where the kneecap is essentially two pieces of bones fused together, which occurs in approximately one per cent of the population

He notices that my shoulders naturally roll forward, likely a consequence of an office job, and I have a slight weakness in my right-hand side compared to the left. The muscular skeletal strength and conditioning tests that follow confirm this. The three tests are simple: a press-up test (how many can I perform in two minutes), squat test (following the same format as the press-up test) and core test (how long can I hold the ‘plank’ position) give a snapshot of my upper body strength, lower body strength and core stability. My body naturally sags to the right during the press-up and core tests, says Webster, and my right foot rolls a little during the squats.

I admit to a genetic condition called bi-partite patella, where the kneecap is essentially two pieces of bones fused together, which occurs in approximately one per cent of the population – including Wimbledon champion Andy Murray – of whom most don’t know they’ve got it. I do, as it caused some discomfort in my right knee as a teenager, and immediately Webster has assembled the first part of the jigsaw. “We can give you a strength and conditioning programme to help address that muscle imbalance,” he says.

I then give a urine sample to provide a snapshot of my hydration status before the second performance-focused half of the test. Webster takes my blood pressure twice, measures my resting heart rate and uses a spirometer – a small handheld device with a mouthpiece at one end which I blow into – to measure my lung function, including lung capacity and peak flow. My lung capacity is slightly above average for my body size, I’m told, and my peak flow is good but not exceptional.

Then it’s on to the Wattbike to look at my pedaling technique. “There’s no point doing a lactate threshold test if you’ve got bad technique,” says Webster. The bike is rigged up to a widescreen television which displays what Wattbike call the ‘Polar View’. It shows the force applied to the pedals and the position of the pedals when applying that force. The screen also shows the force of each leg as an overall percentage, which may or may not highlight an imbalance in leg power.

A peanut shape is considered good, as it shows the cyclist is able to maintain momentum between leg drives, and its a shape I’m naturally able to achieve with a fairly even balance in leg power, but a fatter sausage is the ultimate goal and is a shape labelled ‘elite’ by Wattbike. It shows the rider has a consistent, balanced pedal stroke, with a strong drive and balanced recovery, and Webster gives me a few pointers in order to achieve that shape.

The Wattbike is used widely by British Cycling and offers an incredibly realistic pedaling sensation. In this setup it offers instant feedback and I’m able to work on my pedaling technique while watching the shape on the screen change, for better for worse.

“Try kicking through the front of the shoe at the top of the pedal stroke in order to start the drive phase earlier,” says Webster. I respond and the peanut widens, morphing into something that can perhaps be considered a sausage. It’s difficult to maintain, the increased momentum raises my cadence and, with it, power, but that’s the point. It shows how pedaling technique is intrinsically linked to power and I have something to work on when out on the bike. “Think about it when you’re climbing,” says Webster. “Try and get the power on quicker at the top of the pedal stroke. That will engage your glutes when you’re climbing in the saddle.”

Lactate threshold is the point at which your muscles accumulate lactic acid quicker than they can absorb, or dissipate, it and is a key measurement in regulating effort

The 20-minute session effectively serves as a warm-up for the lactate threshold test that is to follow. Lactate threshold is the point at which your muscles accumulate lactic acid quicker than they can absorb, or dissipate, it. A rider can sit just below their lactate threshold for a time trial but go above it and they won’t be able to stay there for long – the legs will burn, the lungs will rasp and, inevitably, the rider will ground to a halt within minutes if they try and maintain that pace.

“Most of us will know what it feels when we reach or go beyond our threshold,” says Webster, “but by knowing the exact point where you exceed your threshold you can make educated decisions to regulate effort, whether to exceed your threshold and by how much.

“I always compare it to a hill on one of my regular riding routes. I can choose to push as hard as I can up the hill exceeding my threshold but get through the hill with gritted teeth, then allow for a drop in gears and speed for the next few kilometres, or I can ride up the hill using my gears and cadence, not exceeding my threshold and importantly not having two kilometres lactate exhausting to do once I reach the top. Slow can mean faster with the right know how.”

I strap on a heart rate monitor, begin pedaling on the Wattbike in what feels like an easy gear and am asked to maintain a steady cadence at 90 RPM. After two minutes Webster pricks my finger and takes a small blood sample to determine my blood lactate concentration. He notes the recording, along with my heart rate and power, and increases the resistance. It’s essentially a ramp test and the process continues, with a blood sample (my finger only needs to be pricked once, at the start) every two minutes, followed by more resistance.

My first lactate reading is high as a consequence of my earlier warm-up as my body is playing catch-up but it plummets on the second reading. It’s an ‘exhaust’ reading, says Webster, and demonstrates the benefit of a warm-up. It allows the body to acclimatise to the effort that is to come and so it comes as less of a shock to the system, particularly when racing or riding a time trial.

From there the intensity continues to increase over several two-minute steps and, with it, my heart rate and blood lactate concentration. Each step gets progressive harder but it’s an incremental process until I get close to my lactate threshold. By now I’m more than 10 minutes into the test and am beginning to feel very laboured – the difficult is maintaining the required cadence despite the increase in resistance. I try and draw as much oxygen as I can from every breath in order to fuel my aching muscles. Webster takes another blood sample, looks at the reading and says, “I think we’ll reach lactate threshold with the next one”, before ramping up the pressure once again.

I push on, fuelled partly by the pain but also by adrenaline and a competitive instinct which says I should stop only when my body says so

The change is almost instant and my heart rate rises once again and is approaching its max. I’m working hard – very hard – and count down the seconds in my head to the next reading. Webster takes a tiny dot of blood from my finger and the reading confirms I’ve reached my lactate thresold. It certainly feels that way. My legs are now full of lactic acid and I’m struggling to put enough power through the pedals in order to maintain the required cadence. I have a choice: to stop having reached lactate threshold and effectively completed the test or continue, effectively to exhaustion. I push on, fuelled partly by the pain but also by adrenaline and a competitive instinct which says I should stop only when my body say so. It doesn’t last long. The seconds crawl by until the next two-minute marker and, as Webster ramps up the resistance once again and urges me on, I’m unable to maintain the cadence and I collapse over the handlebars in an instant with my heart pounding.

A second urine sample completes the tests – to provide an idea of my rate of dehydration as a result of the lactate threshold test – and I leave tired but eager to find out the results. The tests themselves are a means to an end, and the thoroughness and complexity of the Wilier PPL ‘menu’ means it’s not until I have the data in front of me, and the logic behind it explained, that I will fully understand the reason for each of the day’s steps.

Webster and I meet a week later to discuss the report, though this can also be done over the phone, he says.

“When we finish today we’ll have a programme that you’ll follow,” he says. “The report is detailed but the process is simple. This is the raw data, and I want you to understand why we’ve reached certain conclusions, but it’s important you don’t just leave confused by the data and have something to follow.”

The first part of the report is a lifestyle summary, more relevant, says Webster, if I was 15 stone as it’d enable us to understand why that is and how I’d be able to adapt my lifestyle to change that.

“From your point of view you’re in good shape,” says Webster, “but we can still use it as a snapshot of where you are at this point of time. We have this amazing ability to forget what we were, we can only create a memory of how we felt we were doing at the time, so assuming you gave us honest answers then this is all about knowing where we are now for when it comes to re-test down the line.”

“The report is a snapshot of where you are at this point in time,” says Webster. “This is a reflection of you.”

A traffic light system is then used to display the results of the body composition and muscular skeletal mobility tests. “It’s very rare that we get a report without any red,” he says. There is, of course, significant room for improvement, however. “You’re flexibility is not bad and your upper body strength is good but, as you’d expect, your lower body strength is much better.

“This is a reflection of you. Your strength is derived from what you do every day, so while you’re leg strength is very good, your core is relatively weak in comparison, so we can work on that.”

Webster explains each section in detail, the science behind it, how it relates to me, whether there’s room for improvement and how that improvement can be achieved. The data is comprehensive, covering each aspect of the tests I’d performed a week earlier in detail. The relevance of each section depends on the rider but, core stability aside, one nugget jumps out.

“You’ve managed to get some fairly decent sized lungs in your body,” he says, “and the amount of air you can blow out of your lungs is excellent, but your endurance, how quickly your lungs can deliver oxygen to the blood, doesn’t quite match that level.”

The spirometer tests gave a hint that was the case but the data is verified by the lactate threshold test. Webster gives me two heart rate figures that have been derived from the test: the first is my maximum steady state, which is effectively the effort which I can sustain all day if I take care of my nutrition properly, and a higher figure, my lactate threshold, which is where lactic acid begins to flood the muscle.

“Your ability to work close to your lactate threshold for long periods of time is very, very good,” he says, “but your overall endurance base isn’t quite as efficient.” My riding style reflects that and it’s something we discussed right at the beginning when completing the initial questionnaire. I tend to ride solo, quite hard, for two or three hours at a time, or sprinting between traffic lights when commuting, and enjoy attacking small rises in the road and testing myself on climbs. I also first started cycling with riders stronger and faster than me and had to work outside of my comfort zone to match them.

“We want to improve your efficiency,” he says, “and your ability to produce the same wattage at a lower heart rate.”

It’s the most important part of the jigsaw and will provide the basis of my training to come. First Webster sets me a strength and conditioning programme to complete over the coming weeks in the gym, to improve my core stability and readdress any muscle imbalance, and I will then move into a period of base training to provide the building blocks for next summer’s cycling.

“Your maximum steady state is exceptionally high, which is great as your body has a superb ability to deal with lactic acid in relation to your maximum heart rate,” says Webster.

“We want to improve your efficiency. If we can make your body more efficient leading up to that figure then we’ll be able to increase the wattage you’re able to produce at the same maximum state – and you’ll ride faster.”

And that, after all, is the goal. It means that I am to embark on a structured training programme for the first time in my cycling life and will re-test with Wilier PPL in the spring. It’s an experiment for me, as it would be for any rider embarking on a similar programme for the first time. Will it take the fun out of cycling? Or is the fun in riding fast? The level of commitment is for me to dictate and will develop, for better or worse, over time. What I do know is that Wilier PPL has laid the facts bare and put the data on the table for me to use.

Website: Wilier Performance Progress Lab