Hard training sessions are all well and good, but without sufficient recovery, you’re not going to improve as a rider.

In the previous articles we’ve looked at three principles of conditioning that are key contributors to your training programme. Adaptations are the changes your mind and body go thorough as a result of progressive training overload. In short, by subjecting yourself to gradually increasing ‘stress’ conditions you learn to tolerate the extra workload and you get better at performing the acitivity.

Principle of conditioning 4: Recovery

There is, however, a limit to how much stress you can subject yourself to if you wish to achieve the training target rather than fall short. This limit is the point at which you need to stop training and recover, allowing your body to replenish energy stores, repair or replace damaged tissue and re-focus the mind. Recovery is also the time when the actual adaptations take place. It’s not when you’re subjecting your body to the training but in the downtime, when you are resting and giving yourself the opportunity to adapt to the training load, that you get the benefits of the training.

Many riders have trouble grasping this concept, especially in the initial phases of a training programme when performance improvements come quite rapidly. They respond well to the training and so equate more training with more training adaptation. But this doesn’t work without sufficient recovery periods planned as part of the programme to allow these adaptations to take place.

Continuing to train past the point of fatigue prevents any further adaptations and can lead to reversals. In the worst-case scenario this can result in overtraining, a state of such deeply ingrained fatigue that brief rest periods aren’t enough to recover and several weeks off the bike is required before training can resume.

Finding the optimum relationship between training load and recovery is difficult. You certainly need to push yourself to fatigue by increasing your training in order to improve. This is called ‘overreaching’ and, providing the training load and recovery periods are well balanced, training adaptations will occur and you will see improvements. If the training load is too high, or the recovery insufficient, then they won’t, and you’ll find yourself on a training ‘plateau’ – a state where you simply maintain your current level of performance. It’s quite common to see riders on a training plateau for many seasons as they never change their training methods or apply the principles of conditioning. They enter the same events and get the same results year after year.

Getting the balance between training load and recovery is therefore key and underlines the principle of conditioning we looked at in the last article; ‘progression’ means gradually increasing the training load in order to find the point at which recovery is needed and not completely overloading the system.

Overcompensation

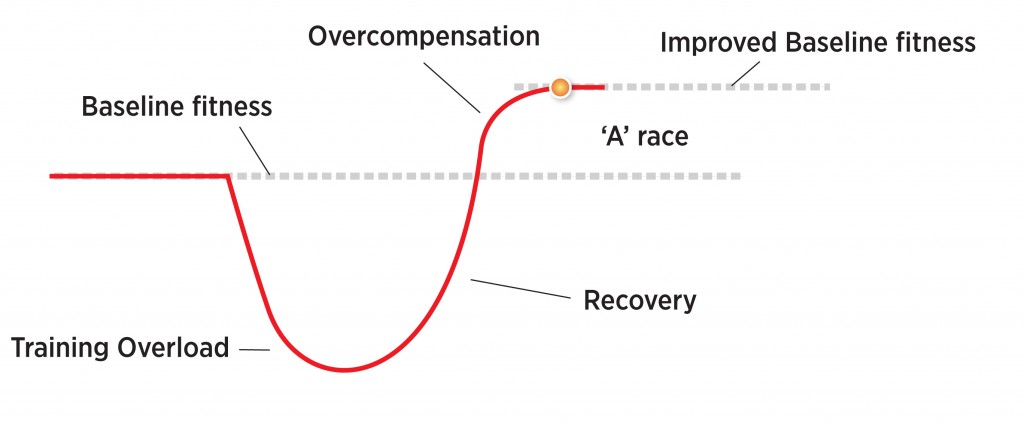

A perfect balance between training load and recovery can be illustrated by the overcompensation model. Look at our diagram 1 and you can see that sufficient recovery following a period of training overload leads to a training effect where you are able to tolerate a higher workload than you could have done previously. This is the training adaptation you are looking for and it’s called overcompensation.

It’s also worth pointing out on this diagram that if riders plan their training correctly, this period of overcompensation will occur at a training ‘peak’ and coincide with a targeted event or ‘A’ race, ensuring that they perform well on the day of the event. You can see from the diagram that your baseline fitness has gone up and, providing you continue with your programme of overload and progression, these adaptations will continue regularly and you will keep seeing improvements, as illustrated in diagram 2 below

If, however, the training load is too great, the recovery period is insufficient or, in the worst-case scenario, there’s a combination of both of these things, then, as you can see in diagram 2, the opposite can happen. So using the overcompensation model you can see that recovery is essential to training adaptations and the correct ratio of training to recovery is very important.

So if this is a given, and recovery periods allow training adaptations to take place, is it logical to assume that if the recovery was ‘better,’ then a return to training could take place sooner, thus speeding up the process of becoming a ‘better’ ride? The answer is a resounding “yes”, which is why riders who pay as much attention to their recovery as to their training sessions have a huge advantage.

There are many ways in which you can optimise the recovery period and get back to training sooner.

Recovery strategies

Recovery can be enhanced in the following ways.

1) Recovery between sessions: Plan your sessions carefully during the week. Avoid the cumulative fatigue of several hard sessions back to back. Split intense sessions with less intense ones to allow recovery and plan days off to allow your body to regenerate. Consider what effect outside influences are having on your training. Do you really think planning for your most intense training sessions to take place immediately after that crucial presentation to your clients at work, which you’ve been working all hours to complete, is a good idea? Plan your week in advance, fitting in sessions as best you can around your work/family commitments, then re-arrange accordingly to afford as much recovery time as possible between your sessions. Also make sure you get enough sleep. Work, travel and even training itself can have a big impact on how many hours you sleep, so keep an eye on this.

2) Nutrition: Good post-training nutrition is essential and speeds up recovery, so eat immediately following your training sessions and make sure you have a healthy, balanced diet in general, based largely on wholefoods, not processed foods. This can be supplemented with isotonic drinks during training sessions that last longer than one hour and recovery drinks such as protein shakes following more intense sessions. Also consume sufficient food and drink when on the bike for endurance rides. Avoid dehydration at all times, even between training days, by keeping your water intake up. A good rule of thumb is that your urine should always be a light straw colour and odorless.

3) Physical therapies: Jacuzzis, hot baths, saunas and plunge pools can all help speed up the recovery of tired, aching limbs. Sports massage is excellent as is self massage, which can be done at home with a little bit of practice. While these hands-on approaches help flush toxins and stimulate blood flow to the muscles there is also a corresponding ‘feel-good’ factor so they contribute to the psychological recovery too. Most important of all though is just get yourself sitting down, ideally with your legs raised.

4) Psychological therapies: Training can be intense on the mind as well as the body, particularly if you’re approaching a big event. There’s a strong relationship between mental and physical fatigue. So practice positive imaging when resting after training, control your breathing and associate the positive images with relaxation and comfort. It all helps get you back on the bike sooner and keeps your training moving forward.

About the author:

Huw Williams is a British Cycling Level 3 road and time trial coach. He has raced on and off road all over the world and completed all the major European sportives. He has written training and fitness articles for a wide number of UK and international cycling publications and websites and as head of La Fuga Performance, coaches a number of riders from enthusiastic novices to national standard racers.

Contact: [email protected]