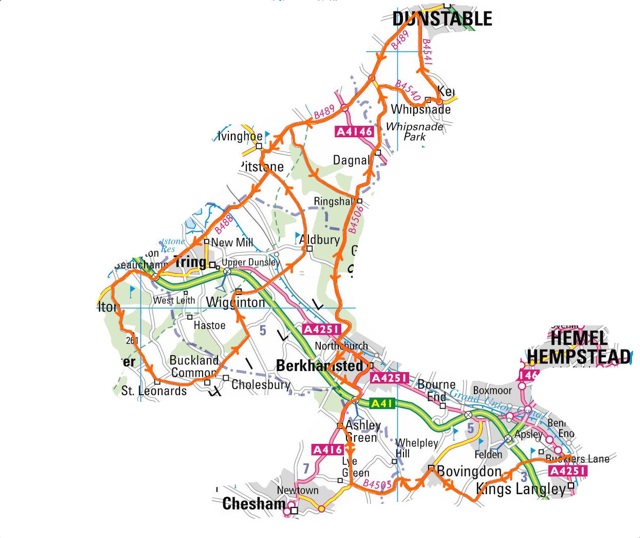

- Pedal force diagram; thanks to Dr Jeff Broker

10 years ago, we at Cyclefit started plying our trade in a relative thought-vacuum about cycling biomechanics. This void gave us all licence to befriend the dangerous twins ‘feel’ and ‘folklore’ when it came to settling our bike-to-body arrangements. Appeals to their close cousin ‘common-sense’ also has risks because so much of cycling biomechanics is counter-intuitive and therefore inherently hidden from our conscious mind.

For example, when we are interviewing a new and injured client, it is very common for all the focus to be on what is perceived to be the ‘problem’ leg and for the other leg often to be described as ‘fine’ or even ‘better engaged’. Only later, when we scan the pedal stroke, do we find that the ‘problem’ leg is doing much of the work compared to its under-achieving partner. The ‘good’ leg feels better because it is relatively under-used and therefore more rested. As I say, this may be considered counter-intuitive because this is not how it ‘feels’ to the rider.

In this series we will examine some myths and assumptions about cycling and juxtapose them with our own experience working with individuals and trying to draw a bead on the bullseye of minimizing injury and pain whilst also increasing power and comfort. In this article we look at an issue that has been especially close to our hearts for every single day of those 10 years because of the potential for efficiency loss and even injury – the Myth of the Upstroke.

The Myth of ‘The Upstroke’

Almost all of us have, at some point in our cycling careers, been coached or advised to pull-up on the pedals by well-meaning friends and peers. And we have all dutifully tried our best to visualize ‘spinning plates’ or similar; because the logic of pulling up is irrefutable. There’s a longer and smoother pedal stroke at the end of the rainbow. Or is there?

Our bodies are perfectly evolved to deal with the ancestral environment of 150,000 years ago, when running and throwing spears was more important than getting gold at l’Etape or winning a race at Hog Hill. As a consequence our pedalling function will always be an extrapolation of our inherited walking or running function.

The Case Against The Upstroke

• Back to our evolved selves – look the image on the left and in particular at the huge mass of the glute muscle – our primary hip-extensors (opening the hip). The glutes make up the biggest and most powerful muscle-group in our body. This is a prime ‘moving’ muscle group, employed in exerting the forces that propel the walker or runner.

In contrast, the image on the right shows the smaller hip-flexors, which pull the thigh upwards. Relatively small compared to the glutes, they are clearly not evolved to produce a huge amount of power. In walking and running the hip-flexors simply move the legs, each lifting the knee towards the chin against the force of gravity acting on that particular leg.

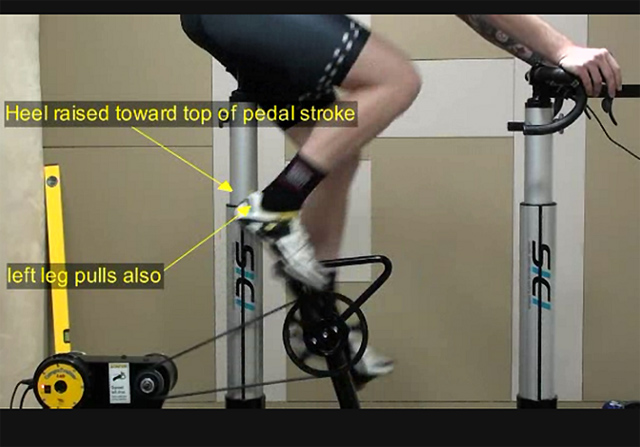

• Unlike when walking or running, where each leg must move independently, in cycling the two legs are linked together by the cranks and bottom bracket axle. Why, then, bother pulling up on the right when you are already pushing down with your biggest movers – i.e the glutes and quads?

• Brain space. It is thought by some earnest biomechanists and cycling physios that we simply don’t have the available neural RAM or proprioception to be able to generate any meaningful force on the upstroke at anything approaching full cadence and full power. Try it for yourself and that is certainly how it feels.

• The research says we don’t – Dr Jeff Broker has done extensive pedalling kinesiology tests on 100 elite and professional cyclists over 10 years and his data shows that not one of them produces a meaningful upstroke. So what hope is there for the rest of us?

Look at the diagram at the top and you will see that even elites and pros have a negative loading on the pedal during the ‘upstream’ or recovery phase of the pedalling circle. That is to say that even they don’t produce enough force at the pedal to offset the effect of gravity on their uphill-moving leg!

Problems Associated with Pulling Up on the Upstroke

Over-use of the hip-flexors when the hip joint is closed can cause all sorts of issues:

• Lower-back pain

• Tightness and pain in the hip

• Loss of power and efficiency

• A feeling of floating or disengagement on one or both legs

• In extreme cases – impingement in the iliac artery!

About the author

A director at London-based Cyclefit, Phil has worked in the bicycle industry since 1994. After switching from being a fairly useless mountain biker to a ‘useful’ 1st Cat roadie, he raced seriously before becoming a vet and retiring to calmer waters. He has also worked as a freelance journalist, contributing articles to Cycle Sport, MBi, Cycling Today, MBR and the US-based Road Magazine.

Having trained at the Serotta Academy in New York and under Paul Swift of Bike Fit bicycle fitting systems, Phil is a European SICI (Serotta International Cycling Institute) Fitting Instructor and Trek Fit Services Instructor.