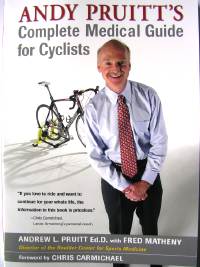

Pruitt – a true specialist |

Who is Andy Pruitt?

Andy is the founder of the Boulder Center for Sports Medicine, in Boulder, Colorado, and a specialist in non-surgical techniques who has treated athletes like cyclist Lance Armstrong and Floyd Landis.

What the pro’s have to say about Andy:

“Andy Pruitt is one of the most knowledgeable people I know when it comes to the physics of cycling and how the human body adapts and changes through years of cycling. With that knowledge he has the potential to help a lot of athletes get better.”

Floyd Landis [no less], Team Phonak

“Thanks to Andy my strength on the bike has increased a lot. He improved and optimized my position on the bike to produce more power, placing less strain on my back, hamstrings, and knees. His expertise will help you get as much out of your bike rides as possible.”

Gunn-Rita Dahle Flesjå, world champion mountain biker

Much has been written about Bike Fit and there are many opinions and views. Andy Pruitt talks a lot of sense here, much of what he says is based in medical research and working with riders with ‘issues’ and those who need to adjust their training and bike fit specifics.

The Complete Medical Guide for Cyclists is published by VeloGear and available from www.amazon.co.uk

We’re very pleased to get this extract… so enjoy.

RULE 1: BIKE FIT IS A MARRIAGE BETWEEN BIKE AND RIDER

When I give talks about bike fit to physicians or cyclists, I often use a photo

of a cyclist dressed in wedding garb with his bike on the steps of a church.

It’s a visual way of reminding people of the importance of compatibility between

bike and rider. Marriage is a strong metaphor for the partnership of

human and machine but it’s an apt one. In fact, serious riders may spend

considerably more time with their bikes than with their spouses!

If you and your bike are incompatible, the marriage will fail. Just as

married couples must adjust to each other, so must a bike and rider.

However, a bike can be adjusted in multiple ways; the saddle can be

moved up or down or the stem can be changed to suit the anatomy of the

rider as needed. But the body can be adjusted only in minor ways—with

a carefully designed stretching program and by adapting to progressively

longer rides. This leads us to the second rule.

RULE 2: MAKE THE BIKE FIT YOUR BODY – DON’T MAKE YOUR BODY FIT THE BIKE

It’s easy to adjust a bike but difficult to stretch or contort your body into

some preconceived “ideal” position. Therefore, it’s important to focus on

making the bike fit you, rather than you trying to match the way another

cyclist rides. For example, if you have long legs coupled with a short torso

and arms, your bike should have a relatively short top tube and stem combination

(often called “reach”). But if you have stubby legs and most of

your height is in your torso, you need a long top tube and stem.

Many riders get their idea of perfect fit from watching pro riders in

person, in videos of races, or in magazine pictures. Then they try to emulate

riders they admire. This is a bad idea for many reasons. Pro riders are

usually lean and lightly built. If you’re not quite as svelte, it’s hard to get

as low and aerodynamic as a pro who isn’t bending over a middle-aged

paunch. Even a fit and lean 50-year-old is probably not as flexible as a

130-pound, 22-year-old professional rider.

The pros are also generally quite flexible because they’ve been riding

competitively since they were young. Their bodies have had time to

adapt to extreme positions that result from the handlebars being much

lower than the saddle.

Finally, pros compete in as many as 100 races a season. Much of their

riding from February to October is spent at the intense levels required by

racing. It’s easier to maintain a low and aero position when going hard;

much more difficult when cruising at a recreational pace. When you cycle

hard, pedaling levitates your body slightly off the saddle and you lean

over into the effort. But when you’re cycling at a moderate pace, you

tend to sit up, which puts pressure on your hands and your seat. As a result,

you’ll feel poor fit faster than the hardworking pro.

So forget what your favorite pro rider’s bike looks like unless your

body and your riding style are carbon copies of his. Make your bike look

like you, not like your hero.

RULE 3: DYNAMIC BIKE FIT IS BETTER THAN STATIC BIKE FIT

Most bike fit systems are static; that is, adjustments are made with a rider

sitting motionless on a trainer or from a set of formulas using body part

measurements. An example is the LeMond Method (see Chapter 2) that

establishes saddle height and frame size from a measurement of the distance

from the pubic bone to the floor.

There’s nothing wrong with these static methods of bike fit. Static and

numerical formulas are an important starting point from which we can

move to dynamic fit. But any static formula is only a starting point.

When you are pedaling, you are constantly moving on the bike. As

you pedal, you actually rise or levitate slightly from the saddle. Therefore

the adjustments made when you’re sitting motionless will result in a different

saddle height than if measurements are taken while you are pedaling.

Reach to the handlebars can change too. When you’re cruising, it’s

easier to reach brake lever hoods that are a bit too far away from the saddle.

But when you’re riding hard, the hamstrings and muscles in the

lower back tighten with the effort, making the bars seem farther away.

Every rider has experienced this phenomenon of the bike “growing” as

the ride gets longer. It’s one reason that while climbing, we tend to sit up

and grab the tops of the bars next to the stem.

At the Boulder Center for Sports Medicine, we use a dynamic system

to determine bike fit variables such as saddle height. First, we attach

reflective markers to specific anatomical landmarks on the rider’s knee,

ankle, and hip (see photo). Then we put him on the trainer and have

him pedal.

We use movement-capture hardware and software to take pictures of the

pedaling rider. The camera emits infrared light to pick up light from the reflective

markers, which are sensitive to infrared. A computer converts the

rider into a 3-D stick figure. From that data we can determine exact and

functional fit for saddle height, saddle fore/aft, and reach to the bar.

When we first developed this system, all the computerized information

had to be entered by hand. Additionally, the bike frame got in the

way of the leg farthest from the camera so its position had to be inferred.

It often took hours to get the data. But now the technology is much

more sophisticated. Results are essentially instantaneous. We can have a

rider converted to a pedaling stick figure almost as soon as she is off the

bike. Finding the ideal bike fit now is just a matter of minutes, rather

than hours.

Again, there’s nothing wrong with static bike fit and mathematical formulas

as a starting place. In fact, in this book I’ll suggest a number of

ways to find ballpark figures for these important measurements. For 95

percent of riders, the information in this book will enable powerful and

pain-free cycling. But if you’re constantly uncomfortable on the bike or

beset with nagging injuries, there’s no substitute for an anatomical dynamic

bike fit done while you’re actually pedaling.

RULE 4: CYCLING IS A SPORT OF REPETITION

A basketball player probably won’t get an overuse injury from shooting.

Even if he hogs the ball and puts it up every time he touches it, that

probably results in only about thirty repetitions of the shooting motion

in a game. And once his teammates are on to him, he probably won’t get

the ball as much!

But cycling, by its nature as an endurance sport, demands continual

repetition of the same pedaling motion for the duration of the ride. At a

cadence of ninety revolutions per minute, a six-hour century ride requires

32,400 iterations of the pedal stroke for each leg. That’s a lot of repetition!

Worse, each pedal stroke is almost identical. Your knee tracks in the

same plane when observed from the front, and it bends the same amount

at the top of each stroke. As a result, a minor misfit (for instance, having

the saddle too low by several millimeters or having one leg longer than

the other by just 5 mm) can lead to major problems over time. That’s

why fit is so important.

Cycling’s repetitive nature manifests itself in the areas of hydration and

nutrition too. Training requires about 600 calories per hour and racing

may burn upwards of 1000 calories per hour. The best conditioned rider

can store glycogen for only two hours of hard effort. This means that only

halfway through a century ride, you’re dehydrated and malnourished! It’s

not just your connective tissue that suffers on long rides.

RULE 5: REMEMBER THE FIT WINDOW

There is a window of good fit on a bike for each rider. I don’t want to

make bike fit sound like a matter of millimeters. Everyone is different,

and even with all my experience I can’t tell you exactly how high your

saddle should be or nail precisely your best reach to the handlebars without

much study of your particular situation.

Most standardized bike fit systems will get you within 2 cm of this fictional

“perfect” fit. At the Boulder Center, we can get a little bit closer.

But over time your body will lead you to make adjustments that bring

you within this “fit window” of a centimeter on either side of your virtual

“perfect” measurement. If you are presently comfortable on your bike,

that’s great. If not, keep working at finding a better position.

RULE 6: MOUNTAIN BIKES ARE AN EXCEPTION

These rules apply to road bike riders as well as people who ride a mountain

or hybrid bike on the road. When riding on a road, your position

stays relatively the same, and you spend a low percentage of the time out

of the saddle. Therefore, repetitive forces are high when riding on the

road.

However, riding a mountain bike on technical terrain like rough singletrack

or rocky four-wheel drive roads lessens the repetition somewhat.

Instead of pedaling with the same motion for hours, you’re bouncing all

over the saddle, standing to get over obstacles, and descending with the

pedals horizontal while using your arms and legs as shock absorbers.

Because of this, fit on a mountain bike is a bit different from fit on a

bike ridden predominantly on the road. For instance, many off-road riders

like their mountain bike saddles about 1 cm lower than they set seat

height on their road bikes. The lower saddle provides a bit more power

for high-torque climbing and makes quick dismounts easier.

But remember the “fit window” of 2 cm. Even if you ride off-road exclusively,

getting a good road fit helps. A good road fit can serve as a baseline

reference. Then you can make modifications for riding off-road from

a solid starting point.

A few more ‘fit specific’ tips when buying a bike:

Saddle position

Saddle position is the key fit variable and the most

important measurement to get right. Both saddle height and saddle setback

are important.

Frames

In the past, frames were designed to allow a large gap—as much as

three inches or more—between the handlebars and the top of the saddle.

Now we’ve come to realize that bars set higher, sometimes almost even

with the saddle, can improve comfort and power production without

compromising aerodynamics.

Layback

It’s a fashion statement in some cycling circles to have

the saddle jammed as far back on the seatpost as possible so the

rider can sport what he considers a “pro” position. But this setback

is right only for riders with long femurs and flexible lower

backs and hamstrings. Be sure your saddle height and setback are correct before

you adjust the handlebar.

Level saddle, or not?

Here’s the rule: If you’re a recreational or touring cyclist and you ride

with the nose of your saddle pointing up or down, your bike doesn’t fit.

The reach to the handlebars is probably incorrect.

In general, your saddle should be positioned level with the ground. It

should not be angled up or down. Check it with a carpenter’s level or by

placing a yardstick lengthwise on the saddle and comparing it to something

horizontal, such as a tabletop or windowsill.

Fork steerer tubes

If you’re buying a new or custom bike, don’t let the shop cut

the steerer tube until you’re sure the fit [height] is right.

Final fit

Remember that even if you had your bike fitted by someone with extensive

training and experience, that doesn’t guarantee the reach will be

right the first time. Because of all the variables that go into it, it’s beyond

even the best bike fitter’s skills to get reach right on the first try. This dimension

is just too personal because of anatomical variables that are not

obvious to the bike shop fitter.

As a result, don’t feel shy about returning to the shop if you realize after

riding several hundred miles that you need a stem change. Riding for

several hours can pinpoint areas of discomfort that weren’t obvious in the

shop the first time. Finding the right reach is a precarious balance, and a

good bike shop will understand this and help you get the fit you need.

Bar width

Handlebars come in several widths. Some manufacturers measure drop

bars from the center of the bar ends, while others measure from the outside

of these openings.

Generally, the bar on your road bike should equal the width of your

shoulders, using the center-to-center handlebar measurement.

Stay safe

You may see some roadies try to get more aerodynamic

by resting their forearms on top of the bar. They grasp the

cable coming from the side of each Shimano brake/shift lever. This

is extremely dangerous! The cables provide only a flimsy grip, so

hitting a bump can cause loss of control and a nasty crash.

Change positions

No matter which grip you use, remember to change it frequently.

If your bike fits properly, holding the bar tops will be as

comfortable as riding in the drops. If you are comfortable only with

your hands in one location, it’s a sign that your reach to the handlebar

is incorrect.

Stem length

Some riders install a long stem with the bar much lower

than the saddle, thinking that this makes them look like a pro. But

the reach is often so excessive that they have to ride most of the

time on the tops with their hands next to the stem. Then they have

to move their hands each time they want to brake or shift.

Modern brake/shift levers are designed to reward riding with the

hands on the lever hoods, where both shifting and braking are

readily accessible. This is, to use a computer term, the default position.

Still, it’s best to change your grip every few minutes to avoid

hand numbness.

Hot foot?

Drilling shoe soles is a last resort. Don’t try it until

you’ve exhausted the other remedies for hot foot in this book.

Drilling can ruin expensive shoes if you don’t know exactly what

you’re doing. In some soles, drilling additional holes can weaken

them. Also, moving cleats far to the rear may reduce “hot foot”

symptoms but create other physical problems as the body copes

with the extreme change in position.

Injury aid

Some injuries respond to focal icing—rubbing ice directly on

the exact spot of the pain. Fill a small paper cup nearly full with water

and put it in the freezer overnight. Once it is frozen, gently massage

the afflicted area with the exposed end of the ice, like you’re

rubbing it with an ice cream cone. As the ice melts, peel away the

paper cup to expose more ice.

Place a towel under the injury to absorb the melting ice. Stop

when your skin begins to get numb. Several five-minute sessions

per hour up to three times a day should provide plenty of therapy

for your ailment without injuring your skin.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: KNEES: How should I care for knees on rides?

There are several things you can do to take care of you knees while you

ride:

is a recipe for trouble. The knee’s tendons lie exposed near the skin’s surface.

temperature is below 65°F.

to get the blood flowing. Start in a small gear and gradually increase both

the resistance and the cadence until you’re sweating lightly and your

knees feel loose. Blasting out of your driveway in the big ring and attacking

the first hill can lead to disaster.

lower than 70 rpm when you’re climbing in the saddle. If you’re standing

while climbing you can go a bit lower, but not much. Low cadences and

big gears are an unholy alliance, putting major strain on knee tendons.

silky smooth.

mileage no more than 10 percent from one week to the next. You need to

let your knees adapt to the workload.

new strains or stresses. If you’ve been riding on flat roads all season, work

into climbing gradually. If you decide to install longer crank arms, don’t

ride 100 miles the first time out on the new equipment. Easy does it. Copyright: Andy Pruitt/Velogear press

The Complete Medical Guide for Cyclists is published by VeloGear and available from www.amazon.co.uk