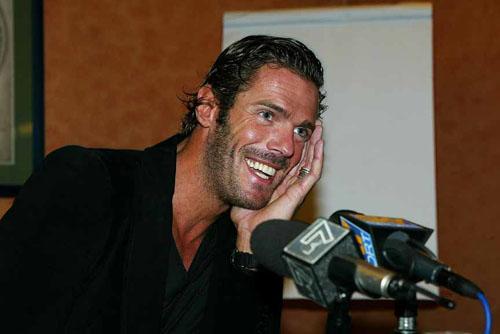

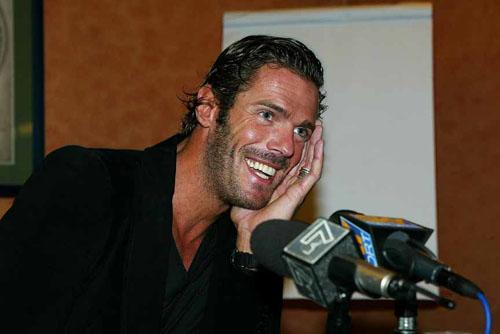

Imagine an athlete with the uncontainable speed of Usain Bolt, the flamboyance of Muhummad Ali, and the suavity of the late James Hunt.

For 15 years, the ranks of professional cycling contained such a man, one who famously instructed his team to dress in togas to celebrate Julius Caesar’s birthday on a Tour de France rest day, and who would send photographs of himself from the beach to Tour rivals suffering on climbs, having accomplished his race mission with stage wins in the opening week.

RoadCyclingUK has been granted the privilege of putting questions to Super Mario Cipollini, aka The Lion King, some of which could be yours. For now, it is our pleasure simply to tell Super Mario’s story, a rich and colourful tale of animal print skin suits, pre-race cigarettes, the possible invention of the sprint train, and 191 victories in a 15-year career at the peak of professional cycling.

Born in Tuscany, Cipollini made his debut at cycling’s elite level in 1989 with the Franco Ballerini-led Del Tongo team. His impact was immediate, claiming a stage win in the Giro d’Italia, before doubling, trebling, and quadrupling his tally in consecutive years, laying the foundations of a record-breaking 42 stage victories in his home Grand Tour, surpassing Alfredo Binda’s record. With eight Giro stage victories in four years on his palmares, by 1993 a win in the Tour De France seemed long overdue. Cipo duly obliged with victory on stage two, where he outsprinted his rivals to cross the line first into Les Sables-d’Olonne. The victory marked the beginning of an on-off affair with cycling’s biggest race which between 1995 and 1999 brought him 12 stage victories, six days in yellow, two days in green, and, in 1999, a post-war record of four consecutive stage wins, including victory in the Tour’s fastest ever stage, raced at an average speed of 50 kmh.

But despite his success at Le Grand Boucle, Cipollini’s colourful personality meant he was not always considered an asset to the Tour, and from 2000 to 2003, a period during which he spent a year in the rainbow bands of world road race champion, he was not invited to cycling’s biggest race.

The Tour’s organizational hierarchy considered the charismatic Italian a mixed blessing. His open disregard for the mountain stages ruffled feathers, and his famous toga party celebration on the 1999 Tour’s rest day at Le Grand Bornand widened the rift with its powerful traditionalists.

Cipo’s success was not limited to the Grand Tours, though cycling’s biggest stage races were undoubtedly Il Leone’s happiest hunting grounds. A record-breaking three victories in Ghent-Wevelgem (1992, 1993, and 2002) proved his ability to win amid the early-season slog of a Belgian classic, as well on the sun baked roads of France, Spain, and Italy.

His addition to the Ghent-Wevelgem record books in 2002 would prove to be only a staging post in a season remarkable even by Cipo’s standards. The year began with victory at his home classic, the Milan–San Remo. La Primevera contains the decisive climbs of the Cipressa and the Poggio, requiring the victor to survive the steep ramps of northern Italy to triumph. Cipollini’s victory in the colours of Acqua-Sapone followed Paulo Bettini’s failed attack on the Poggio. Once his compatriot, and future double world champion, had been swept up on the descent, Cipollni’s sprint train led him home to secure, at 35, a remarkable victory.

This brilliant start to what was to become the Italian’s greatest season (a further six Giro stage wins added to his two victories in the spring classics) was almost derailed by another falling out with the Tour De France hierarchy, and a characteristically impetuous decision to retire. His decision was reversed by the persuasion of Francesco Ballerini, the Italian team manager, who, recognizing that Cipollini’s speed remained untouched by his advancing years, staked the efforts of a team packed with sprinting talent, including a young Alessandro Pettachi, on the charismatic veteran. In a precursor to the Great Britain team’s ride in support of Mark Cavendish at Copenhagen last October, the Italians controlled the race by setting an impossibly high tempo before launching Cipollini off the front in the closing metres. Rising brilliantly to the occasion, Cipollini, crossed the finish line in the Belgian town of Zolder ahead of two more supreme sprinting talents, Erik Zabel and Robbie McEwan, at the end of 185km raced at an average speed of nearly 46kmh.

Cipo retired again a week before the 2005 Giro, and remained so for three years, before returning to the Pro Tour peloton in 2008 with Rock Racing, finishing third on the second stage of his comeback race, the Tour of California. His return to action would prove short lived, however. A dispute with the team’s hierarchy led to his definitive retirement the day before Milan-San Remo.

A quiet withdrawal from the spotlight was never likely to be Cipollini’s style, and he has remained as outspoken in his retirement as he was during his career. Cavendish, Contador (“Contador has the anonymous face of a surveyor or an accountant”) and Andy Schleck have all been subjects of Mario’s ire, and while criticism, especially of Cavendish’s extraordinary achievements, can usually be ascribed to professional jealousy, Cipollini has a palmares to compare to anybody’s. Fans of professional cycling can only imagine who would have triumphed in a showdown between Super Mario and the Manx Missile. One thing is certain: no-one else would get a look in.