So far in this series, we’ve identified six components of fitness that, depending on the event, every cyclist needs to develop to a greater or lesser degree in order to be well adapted to perform in that event. We’ve looked at Aerobic Endurance, Speed, Strength, Power, Flexibility and STME. But we finished last week with the very important observation that focusing on the components of fitness alone is not sufficient to make you the rider you really want to be. For that, you also have to consider the tactical, technical, psychological, nutritional and even mechanical elements that need to be in place to allow you to perform at the best of your abilities. In the coming weeks we’ll be looking at all of these elements in more detail.

When looking at the sheer range of the things they might need to work on, it’s no wonder that many riders fall into a kind of ‘option paralysis’ – a state whereby, given so many options of what to do, they end up unable to choose any, and do nothing at all. In riding terms this translates into simply carrying on as you were, riding your bike as often as you can and as fast as your current level of fitness and technical ability allows. There’s nothing wrong with this, after all you’re still riding your bike and pursuing an active lifestyle which is the main thing. But look at the headline of our series… ‘Training for Results’ and you’ll understand why you can do better than simply ‘riding your bike’ if you want to be a ‘better’ rider.

So the key to becoming a better rider is identifying the things you need to work on and improving on as many of them as is possible. Your chosen event will dictate to what extent each of these elements needs to be developed, but whatever your area of interest, there’ll be a lot of things you can do to improve. So how do you juggle all the various training sessions, components of fitness, technical skills and everything else you need to do to fit them into a manageable training programme? The answer is a system called ‘Periodization,’ which in simple terms means splitting your training year into ‘cycles’ of shorter, more manageable chunks, where you work on a few of the requirements at a time before moving on to the next ‘cycle.’

Looked at in this way, your training doesn’t seem half so daunting. You can, for example, take a training year and refer to it as a Macrocycle. Split this Macrocycle into six two-month blocks and call these Mesocycles. Take these Mesocycles and further subdivide them into Microcycles and you have the basic outline of a periodized training year that looks like this:

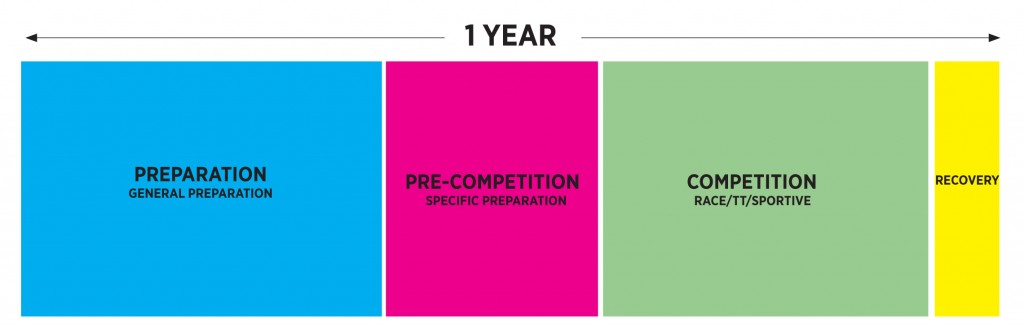

You can immediately see from this the opportunity to ascribe certain cycles of the training year to the various elements of your training that you want to work on. But let’s ditch these traditional terms of Meso, Macro and so on and split the year a bit more meaningfully, like this:

Now we have some terminology that makes a bit more sense – you can see certain periods of the year set aside for preparing for your events in a general sense, then preparing a bit more specifically, before actually competing in them and finally having a bit of a rest after all that activity and preparing for the following season.

Now we’re getting somewhere. We can now take the preparation phase and use it for your general conditioning work; things like the aerobic endurance component of fitness as well as bike handling skills and core strength work traditionally fit well into this period.

After a solid block of preparation work you’re ready to move on to more specific conditioning. As with all of these ‘phases’ of your training, your events dictate what you work on, what time of the year you do so and for how long. In any case, generally speaking the pre-competition phase would involve an increase in the intensity of your training as the events themselves approach along with a lessening of the longer aerobic endurance work to facilitate the switch to shorter harder training sessions, which might target speed and power. Technical work would also reflect the approaching events with more emphasis on event -pecific drills. Finally, you’d have the competition phase itself where the majority of your events take place.

So that’s a very basic periodized training year. I say ‘basic’ because it’s almost never as straightforward as it appears here. There’ll be events you want to do in the middle of the preparation phase, for example. Or you might want to race cyclo-cross in the winter to retain your fitness, so what does that do to your annual plan? And how can you put a preparation phase of long endurance rides in place if there’s snow on the roads for eight weeks out of the 12-week block you had planned?

All of these things occur in the real world but can be overcome with good planning and an understanding of periodization. So simply start by looking at a year planner, filling in your events and working out a rough idea of what you need to work on in training terms and what times of the year you intend to do it. When you have a basic periodized framework in place, balancing the many elements of your training becomes far less daunting and far more manageable.

Next week we’ll start looking at how you use your training time within these periods and what you need to do to ensure you get the most from your training time.

About the author:

Huw Williams is a British Cycling Level 3 road and time trial coach. He has raced on and off road all over the world and completed all the major European sportives. He has written training and fitness articles for a wide number of UK and international cycling publications and websites and as head of La Fuga Performance, coaches a number of riders from enthusiastic novices to national standard racers.

Contact: [email protected]