Picture this: a €15,000 superbike, with a carbon chassis woven in Europe rather than moulded in the Far East, and identified not by anything as garish as branding, but by a signature.

This same signature appears on the components: a Clavicula crank, Lightweight wheels, a Fizik saddle. The bicycle is black and the signature is white. It says simply, Time No.6. Henri Colliard, Vice President of Global Development, has ambitious plans for Time Sport. “We are Aston Martin,” he says. “We are Dior.”

Founded more than a quarter of a century ago by Rolland Cattin as the manufacturer of a clipless pedal that quickly became the choice of Grand Tour champions, Greg LeMond and Miguel Indurain, Time moved into making carbon forks, another hit with the peloton, and later complete framesets, ridden to world and Olympic titles by Paolo Bettini and to world and Monument Classic triumphs by Tom Boonen.

A former CEO of the surf brand, Rip Curl, a mountain biker and rock climber, and a Frenchman with a passionate belief in manufacturing in his own country, Colliard has joined Time Sport with a clear vision of the market position he believes the brand should occupy.

Concept stores are at the heart of his plan to return Time to what he believes should be its natural position. They will be called Timexperience No.6, the numeral a nod to carbon’s position on the periodic table. The stores will be black and white, with black representing Time’s carbon chassis, and white the accessories and apparel of a host of elite brands Colliard has recruited as partners Lightweight, Mavic, Casco, X-Bionic, Oakley, and Corima.

He hopes to open 15 concept stores within the next three years in key markets including France, Great Britain, Japan, and the USA. Bikes will be displayed as Christian Dior displays a bag, he says, or as Rolex displays a watch. The stores will be franchised and while the owner will pay for the fitting of the premises, Time will supply the stock. The owner will invoice Time monthly for payment on the goods sold in a relationship Colliard describes as “commission-affiliation”, which he says is commonplace among leading fashion brands such as Lacoste, Quicksilver, and Esprit.

The product that underlies such ambition must necessarily be of high quality. So how does Time support its claims for a place among the world’s most exclusive brands? Carbon technologies including Resin Transfer Moulding and Compressed Moulding Technology lie at the heart of its offering. We travelled to Time’s facility near Lyon to make a detailed inspection of the production process.

Fruit of the loom

First among Time’s claims for quality is the Resin Transfer Moulding process. Where the tubes for many frames mass produced in the Far East are typically made from sheets of carbon pre-impregnated with resin, Time’s are woven from individual strands of carbon fibre on giant looms.

Watching the looms can be a dizzying experience. The bobbins dance with a speed and precision almost impossible for the eye to follow. The thread with which each reel is loaded, variously carbon, vectran (to reduce vibration in the finished product), elastene, and Kevlar, feeds through a small aperture at the top of the machine where it is entwined with numerous others.

The machine extrudes a carbon sock, compressed then into what looks like a tape by giant rollers whose unhurried progress forms an amusing contrast with the agitated bobbins below. The carbon tape/sock, seemingly mile-upon-mile of it, falls slowly into a humble cardboard box.

Their cumbersome appearance speaks of heavy industry and unsophisticated engineering, but the looms, and the different weaves they spin, are intrinsic to the ride characteristics of the frame. Each loom is used for a different section of the frame, and is equipped with between 16 and 120 bobbins, depending on its purpose. Smaller machines with fewer looms are used to create the bottom bracket and chain and seat stays; large machines spin the longer ‘socks’ that will be used for the front triangle.

The angle of the threads is carefully controlled, and set between 15 and 70 degrees: smaller angles create greater torsional rigidity in the resulting tube, while greater ones permit more flexibility. Unidirectional fibres are used where the frame is likely to be subject to the greatest forces; bidirectional where stress will be lower.

Lay-up

Once the carbon has been woven, it is taken to the cutting room. The women who staff the department wield their scissors with impressive dexterity, trimming the carbon sock to the length required to fit the various wax moulds that form a skeleton, and which will later melt from the newly-hardened carbon skin in a process known as ‘wax loss’.

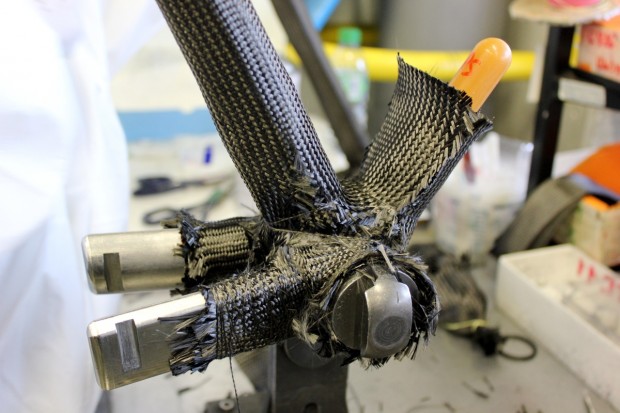

The layering of the carbon is a fascinating process to watch. Each piece is moulded individually. The most intricate section is the union of fibres required to create the bottom bracket shell. Thirty-two layers are used for this area, which includes the lower sections of seat and downtube and the foremost section of the chainstays. The process is finished with the winding of a single carbon strand around and around the carefully arranged layers.

Different workers at different stations work on different areas of the bicycle, and the lay-up differs for each of the models that Time produce. While one worker creates the aforementioned bottom bracket area, another constructs the front triangle – the head tube and the foremost sections of top and down tube – pulling the carbon sock over the wax mould and, again, securing it with a single strand of carbon thread.

Finally, a cosmetic layer of pre-preg carbon is applied to the frame by a woman wearing a mask and gloves and wielding a gun breathing out air heated to 360 degrees. This layer has no structural quality, only aesthetic.

Resin Transfer Moulding (RTM) has been Time’s signature for many years, and one they claim has greater structural integrity than a frame made entirely from sheets of pre-preg carbon. In short, the carbon sock has no join.

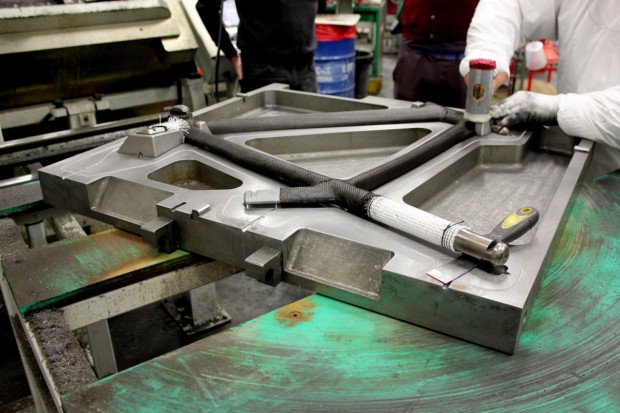

The carbon-covered, wax structure of the front triangle is placed in a mould resembling an aluminium suitcase. The ‘case’ is closed, and tilted to an angle by a giant robot. An 800g mix of resins is injected into the carbon (though not into the wax skeleton) through a single entry point in the case and heated to 100 degrees – critically, a temperature below the 140 degrees required to melt the wax.

Of equal importance is that the injection is completed without the unwanted ingress of air, an element that can create voids: a frequent failing with pre-preg carbon. The resin is pumped through the carbon and the excess extracted at a pressure of four bar, increased to six if an air bubble is suspected. Such pressures are far greater than those achieved by the use of inflatable bladders placed inside the frame, another popular technique.

Excess resin is extruded from the mould through three clear, plastic tubes. Once the flow is exhausted, the process is complete. The engineer removes the frame, which has taken on a glossy aspect, from the mould. The tubes are warm to the touch, radiating heat from the wax skeleton beneath the newly-baked carbon skin. A bar code on the inner plane of the non-driveside chainstay records when and by whom the frame was baked. Colliard plans to increase Time Sport’s quality control tracking procedures by inserting a microchip into the frame. Eight frames are ‘baked’ each day, and between 70 and 90 are produced each year.

The skeleton is removed in a proprietary process that we weren’t allowed to photograph, and the wax recycled. We were, however, shown how the wax moulds are made. The procedure is similar to the RTM process described above, with wax ‘baked’ instead of carbon.

CMT

Compressed Moulding Technology is the other process we are not allowed to photograph. Colliard claims Time Sport is the only manufacturer in the cycle industry using the technology, which involves freezing and heating swatches of carbon. Boeing, he says, used the process to create the window frames on the 787 Dreamliner.

It is used only for small components, in which short fibres are used, such as fork dropouts and the face plates for Time’s carbon stems. The carbon is compressed, and frozen to retain the necessary density, before being rolled and moulded. Pressure here is crucial: 10 tonnes is applied to the aluminium mould in which they are shaped. The carbon is bought in by Time, rather than woven on the looms from which the frames are created, but a secret ingredient specified by the R&D department is added.

Having been frozen, the moulded components are heated to temperatures of 120 degrees. The larger components are baked for up to 600 seconds. Once baked, the components are held in an aluminium jig to prevent further contraction or expansion.

Quality control is crucial. Failure of the components made using this process could be catastrophic for the rider. The slightest imperfection means the product is binned. Temperature and moisture in this segregated area are tightly controlled to ensure consistency of manufacture throughout the year. The material must be used on the day it is prepared. CMT is not a cheap process.

A solid bond

The two halves of the frame, front and rear triangle, baked separately in the RTM process are bonded together by hand in the collage department and mounted in a jig overnight. It’s here also that the aluminium cups for the bottom bracket and the Safe+ compact bearings of Time’s patented Quickset headset are installed.

The engineers mix a fine black paste, which is applied with a spatula to the outer edge of the cups and pressed into the headtube and bottom bracket shell. Once the bonding of front and rear triangles and of the inserts is completed, the frame is placed in a huge oven and dried.

The most notable feature of the sanding room is the noise. Each frame takes 45 minutes to prepare. It’s a tough job. Any imperfections exposed in the frame, fork, stems or any other carbon product made in the factory lead to them being scrapped immediately.

Further examples of Time’s quality control can be found in the stress testing department, where frames, forks, handlebars and stems, already painted, and, in many cases, decaled too, are gripped by machines and flexed remorselessly. It is easy to describe the process as inhuman, given the mechanical nature of the test, but that observation is undercut by the ‘breathing’ of the compressor-driven pistons and the movement of the components, especially of the handlebars, which respond, necessarily, as if held by human hands. It is a strangely disconcerting vision.

Four levels of finish are offered. Black Label and VIP finishes carry an additional charge of €150. The VIP finish, for example, offers painted logos rather than decals. The water-based decals, however, are applied with no small skill. Once finished, the frames are varnished. Painters work in protective masks and white suits, visible in their sealed booths through fogged panes of glass, wielding their airbrushes with obvious skill.

Part of the investment in Time’s new retail strategy will come from money saved on its cancelled sponsorship of the Saur Sojasun WorldTour team. Time supplied the team with 220 bikes last year, a requirement Coillard says halted supply to the retail market for six weeks. A return to racing has not been ruled out entirely, but will not happen this year or next.

While assembly is the final stage of the process, RCUK’s visit ends with a ride out aboard a finished bicycle. Mont Blanc is visible on the horizon beneath a glorious blue sky, and, it must be said, the ride quality delivered by our borrowed steed (a recent, but superseded model) is excellent. With cutting edge technologies and a bold new marketing strategy, Time will hope to regain the prestige accrued from the success of Bettini, Boonen, Indurain et al.

Website: Time

UK distributor: Extra UK