There’s been a lot of talk on the RCUK forum of late about the merits of commuting as part of training. Specifically, whether it’s possible to gain any real training benefits and fit any kind of structure into rides that are at best random due to the unpredictable nature of riding conditions on roads subjected to heavy volumes of traffic and with regular interruptions such as traffic lights and junctions.

The need to include commuting time as part of training is understandable. Given the time restraints these days put on the lives of many people in full time employment, commuting is often a necessary and essential contributor. The good news is that commuting can offer valuable on-bike training time, provided you use it well. So here we’ll look at a number of ways in which the regular, daily commute can be turned into training.

Bear in mind that this is not a guide to commuting, rather than how to use commutes as training, so it assumes you already have suitable knowledge and ability to interpret road and traffic conditions that allow you to do these without endangering yourself or other road users in your very selfish pursuit of improved performance. I’ll also state here that I and a number of very good road racers I know use all of the below workouts regularly and we commute into central London – so we if we can do it, chances are you can too.

We need to start with a definition of ‘commuting’, as clearly any ride that takes place on beautifully traffic-free roads can be used as part of your regular training regardless of what time of day or what your destination is. ‘Commuting’ in the context of this article is a journey through built-up areas, towns or cities affected by traffic, lights, road works, and junctions that doesn’t afford the kind of uninterrupted riding time offered on open roads or indoor trainers.

The first thing to do in order to use commuting as part of your training is to stop thinking of it as commuting. Think of it as training time, the same as any other training time you have available. As with any training, in order get the most out of it, you have to apply the principles of conditioning that we’ve been looking at in our training for results series. That means you need to have some way of measuring what you’re doing in your commutes before overloading and progressing on it in order to see training adaptations. The only significant difference is that you clearly have to base your training on much shorter intervals in order to account for traffic and road conditions.

So what we need to do is apply our principles of conditioning to the commute and target the components of fitness we identified as being essential to cycling performance. You may recall that these are aerobic endurance, speed, strength, power, short-term muscular endurance (STME) and flexibility.

Right off the bat I’m going to drop flexibility from the list of things to practice DURING your commutes as, unless you have developed a special technique for performing cycle-mounted pilates or yoga, you’re unlikely to be including any flexibility routines in your ride to work (hopefully). Commuting does, however, underline how important flexibility is in more general terms as you need good rotation of the head, neck and upper body in order to stay aware of traffic conditions on your commute. So my advice is, if you’re commuting, include regular flexibility exercises to facilitate this if you’re not doing so already.

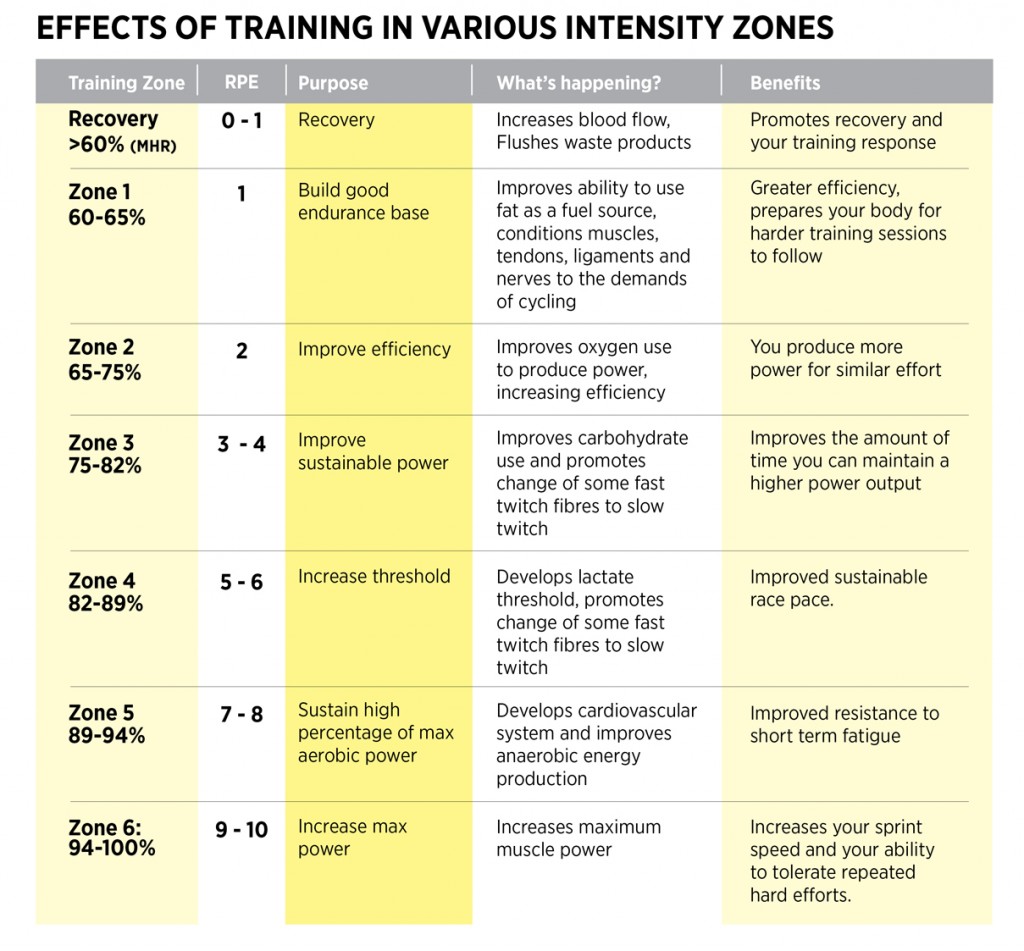

We’ll begin with a reminder of training zone intensity based on a percentage of our maximum heart rate…

Now I know what you’re thinking… “How is a training zone relevant to my commuting rides if I can’t ride for more than a few minutes without interruptions?” A good question, but the point is that all these training zones have benefits associated with them (as you can see in the table above) in terms of improving your cycling fitness. From the very easy pace of the ‘Recovery Zone’ to the eye-watering neuromuscular maximal sprint intensity of Zone 6, as long as you’re riding your bike you will be riding within one of these zones and therefore have the opportunity to gain some kind of training benefit from it. The key is trying to find some structure within the seemingly random series of ride/stop/start, ride/stop/start intervals of activity of varying duration that commuting demands.

Component of fitness 1: Aerobic endurance & commuting

This kind of training is normally all about long hours of riding at relatively easy intensity intended to develop all the elements fundamental to good endurance as listed in zones one and two above. But let’s first look at an even easier intensity: the Zone 1 recovery ride.

This is ultra easy-paced riding and, as the name suggests, is used for little more than recovering from other, harder rides. Active recovery is better than passive recovery (e.g. sitting on the sofa), so commuting rides at this intensity can be a highly valuable part of your commute if you are training hard in other sessions. It simply means that, instead of adding further fatigue, following harder weekend and evening sessions, you are actively using the commute to recover without risking inhibiting performance in other sessions. Remember a couple of weeks back we spoke about the principle of conditioning which is ‘Recovery’? Well, here’s your chance to do it AND keep riding the bike AND get to work on time. Can’t be bad eh?

How do you do it? Discipline is the key here. You’ll be tempted to go too fast because other riders will be passing you. Another point is that you’d be surprised at how much harder constant efforts pulling away from traffic lights in high gears are than you might think. You might not notice this on a heart rate monitor due to its slow response time but try commuting with a power meter and you’d be surprised at the cumulative effort you have to make when constantly stop-starting. So keep things VERY easy in order to get genuine recovery benefits.

At slightly higher intensity are Zone 1 & 2 aerobic endurance rides, which are often done over several hours. These are clearly out of the question here, but regular commutes at this intensity can combine to offer aerobic endurance benefits. Think of the cumulative effect rather than individual ride time. If, for example, your commute involved 2 x 45min rides from Monday to Friday, you’d have amassed 7.5 hours at Zone 2 pace. Not an insignificant amount, particularly if you are then working on your aerobic endurance fitness at the weekend. Two rides of 2-3 hours each day on Saturday and Sunday would put you in the region of 12 hours for the week and that is a very respectable amount of aerobic endurance hours for someone who works full time.

There’s better yet to come. The aerobic endurance end of your training intensity is also a great time to develop the technical elements of riding that many riders struggle to find time to fit in. Not least of them is…

Component of fitness 2: Speed & commuting.

Now before you get all health & safety conscious on me, ‘Speed’ as a component of fitness is about leg speed or cadence, not trying to break your PB for how fast you can get to work every morning. Developing good cadence is a very important part of cycling and many riders spend far less time developing it than they might. So some of your ‘dead’ hours of commuting can be of great benefit if you use them to develop your (Leg) speed.

Typical workout: Cadence pyramids. Identify a part of your ride where you can do a few intervals of one to two minutes uninterrupted and, when you get there, spin a gear that allows you to get up to 90rpm without raising your effort level out of Zone 2 for 60 seconds. Easy? Ok, after a minute of normal pedaling, or when road conditions next allow, add on 10rpm and go for another minute, this time at 100rpm, without raising the effort level out of Zone 2. Fit in as many of these as you can, increasing the cadence until you start bouncing uncomfortably in the saddle. This is the point that you become inefficient so come ‘back down’ the pyramid.

Let’s say you got to 120rpm and started to get uncomfortable, the next 60 seconds should be 110, then 100 and so on. The reason for putting the Zone 2 ceiling on it is that you are still working at your aerobic endurance intensity and, more importantly, this demands a gear so ‘easy’ that you are not careering towards the No9 bus at 35mph. Do this once or twice per week, count the number of pyramid intervals and cadence you are doing and you’re not just commuting, you’re improving a key component of fitness AND working on your aerobic endurance. That’s not a bad start to the day and as your efficiency improves you haven’t even got to work yet! Over time you’ll see your cadence get higher and higher before you start to feel uncomfortable.

Component of fitness 3: Strength & Commuting

Defined as the amount of ‘force’ you can apply to the pedals, strength is a very important component of fitness for cyclists and, in tandem with the one above, ‘Speed’, creates number 4, ‘Power’, but more on that in minute. Strength exercises are best done in the gym as the bicycle is too efficient an energy converter to offer serious amounts of resistance.

Even in the hardest gears the pedals move away from you when you press down on them with comparatively little effort. So strength exercises are most beneficial when done against resistance that is less prone to shifting under your weight, such as the floor, when you do squats exercises. That said, you DO need to develop cycling specific strength and that means pedaling in progressively harder gears. Again, commuting rides offer ample opportunities to develop this component of fitness.

Typical workout: On-bike Strength. Using your big ring at the front, drop the chain down four sprockets at the back. Now pedal for 30 seconds in this gear without driving your heart rate above Zone 2. Spin easy for 30 seconds then drop it into one harder a gear and do the same thing. Then after another 30 seconds easy spin one gear harder and the same again. As you’re keeping the intensity level the same but using harder gears your cadence will come down, but that’s good, you’re focusing on your strength here not your speed as in the cadence pyramids.

Do this all through your commute (as long as traffic conditions allow, using the three middle gears on the block). The following weeks, on the same day, add in a 4th gear, one harder. Then the following week yet another gear harder than that. Do this until you are using the spread of gears between the middle of the block and the hardest gear on the bike. So, effectively, you’re doing 30 second intervals in progressively harder gears and improving your on-bike strength. Again, the cap on intensity at Zone 2 and the low cadence this demands means you shouldn’t be going uncontrollably fast, but obviously, keep your head up and safety first eh?

Component of fitness 4: Power & commuting

As mentioned above, this is a product of how fast you can pedal and how much force you can apply to the pedals all at the same time. Power intervals are particularly useful to road racers and, again, commutes are a great place to practice them, as they are short, very dynamic, explosive bursts of energy. Unlike the ‘Speed’ and ‘Strength’ component workouts above, these very much require high road speed and fast acceleration so identifying a suitable area of your commute is essential. But they are very short and more doable than you might imagine even on the busiest of commutes. And if you’re a budding 5th cat racer (somebody who simply MUST race every other rider on the commute) then these will help you ‘win.’

Typical workout: Power Sprints. Roll easily away from a set of traffic lights up to about 10-15mph then jump out of the saddle with as forceful an effort as you can make and try to spin the gear out as fast as you can. Maintain it for a maximum of 20 seconds or shorter if road conditions demand it and come off the power. Do these in a similar progression of gears to the on bike strength exercises but this time the effort is shorter, with a higher cadence and at much higher intensity – its your power you’re working, a combination of speed AND strength.

You’re also developing your neuromuscular facility – how fast you can process the signal from your brain that it’s time to get busy, and recruit your army of fast-twitch muscle fibres into hard, fast action. Try to maintain good form and (obviously on the road) keep a good straight line. These are particularly good if they can be done on a short hill of moderate steepness too. Remember that in all these cases you need to adhere to our principles of conditioning by progressing the session and overloading, so count the number of sprints you do and increase it by one or two each time you feel you’ve become adapted to the current amount.

Component of fitness 5: Short Term Muscular Endurance

STME is, for want of a better description, a prolonged sprint. In other words, it is sustaining a high power output with strong muscular contractions. Clearly as it’s sustained for longer than a sprint that means its not a ‘maximal’ effort but it is still very hard at around Zone 5 on your intensity chart. Pulling away from traffic lights on your commutes affords a great opportunity to develop STME.

Typical workout: Seated Accelerations. Using the same spread of gears as the on-bike strength session, pull away from the lights and, remaining seated, simply accelerate up to high speed as quickly as you can and once there, sustain the effort. Make sure you use a stretch of road that allows one minute at this speed and cadence and you’re aiming for high levels of discomfort. Such is the intensity, you should just about be able to make the one-minute mark. Progress these by using a harder set of gears but also by extending the duration week by week.

So those are just a few ideas for ways in which you can add structured training into your commutes. They are just that, suggestions; hopefully you can identify aspects of your own commute routes that afford opportunities to do these or develop your own sessions targeting your own specific needs. You’ll also make your rides into work a whole lot more fun in the process.

Bear in mind some general rules of interval training by paying attention to your recovery intervals too. A good rule of thumb is that, if you’re training to improve your endurance, then take less recovery time between the hard efforts. This keeps the heart rate high and improves your lactate tolerance. If you’re training to improve peak power, take longer recovery intervals in order to ensure that in the following interval you are able to perform at sufficiently high intensity. Which of these aspects you work on could well be dictated by road conditions, frequency of traffic lights etc, etc.

Finally, bear in mind ways in which you can alter your commute to suit your training needs. Can you stay out longer? Having made the effort to get changed and kitted up, would you be better off setting out 20 minutes earlier and increasing your training volume? A commute needn’t just be from home to work either. Last summer I coached two untrained London riders to complete the Marmotte, one of the hilliest sportives in Europe, largely by amending their commute routes to include twice-weekly sessions on a variety of hills around Highgate and Hampstead. It’s hardly the Alps, but you use what you have.

About the author:

Huw Williams is a British Cycling Level 3 road and time trial coach. He has raced on and off road all over the world and completed all the major European sportives. He has written training and fitness articles for a wide number of UK and international cycling publications and websites and as head of La Fuga Performance, coaches a number of riders from enthusiastic novices to national standard racers.

Contact: [email protected]