We arrived in Paris from London at midnight; eight hours later we met Chris Ragsdale for the first time. Tarik (of Etape Reine Cycling) and myself were to be a two-man crew in his attempt to clock the fastest time at Paris-Brest-Paris 2011. Chris is a multiple US 24-hour champion and world record holder for the 1,000km. This was his first time attempting the 1,200km event, and our first time crewing. Despite our research none of us had a real idea of what to expect – the following two days and nights were to expose our naivety.

Paris-Brest-Paris is the world’s oldest cycling event. From 1891 until 1951 it was ran as a professional race, but since then it has been classed as a randoneur open only to amateurs. But forget all your preconceptions about audax and long distance cycling with its image of old men in beards and sandals, P-B-P is still a race for those at the front, and still as competitive and fiercely fought than ever.

The fastest riders will tackle the 1,200km without breaking for sleep, aiming to finish within about 45 hours. The only stopping will be at the control points spread along the route, mostly 50-80km apart. At these controls each rider must get his brevet card stamped, and they are also the only opportunities for his support team to offer their assistance, being barred from entering the riders’ route at any other point.

On Sunday morning we headed to the start in Versailles from our hotel in central Paris. Chris needed to be there four hours early simply to get a good starting position. That’s an additional four hours of stress that I’m sure Chris could well do without. After he’d talked us through all his spare kit, attached his rear mudguard in anticipation of the forecast rain, discussed his drinks preferences and how much food he’ll need between each control (calculated on the basis of approximately 300kcals per hour), we set off ahead of the riders to gather supplies and set up ready for the first feed stop at Mortagne-au-Perche, 140km away.

We now had some time on our hands. Supplies were gathered and we started to discover the shortcomings of French supermarkets; limited opening hours and limited choice. We tried to find ice, but with no luck. No such thing as a pre-made pasta, no sign of the meal replacement drinks Chris had requested.

After parking up in the centre of town we tried to grab some sleep, but with the anticipation of what was about to follow all we managed to do was rest our eyes. All the while the town was beginning to fill with camper vans – equipped with kitchenettes, hot water, beds even – bearing the official support vehicle stickers of Paris-Brest-Paris. It was hard not to question our own level of preparation.

Our first crewing duties would consist of simply handing up a musette bag with drinks bottles and food. Straightforward stuff. We awaited the arrival of the lead group just as a barbecue was being fired up in the town square. A small crowd gathered as we peered down the road and the long steep hill that led up to us. A lead motorbike appeared and we got into position. Galloping towards us was a peloton of perhaps 200 riders, strung out with gaps having opened on the climb. We were taken aback by the pace – I’m not sure what we were expecting, but with still 1,000km still to go the effort was already showing on the riders faces.

Chris grabbed his musette from Tarik without incident, and we hastily returned to our car, wary of getting caught in the convoy of traffic that was to snake its way to the next control point at Villaines-la-Juhel at 222km.

Night has drawn in and we’re chasing red tail lights. At least we can’t get lost with so many vehicles heading for the same destination.

Our first impressions of the Villaines-la-Juhel control are of confusion – from which direction are the riders arriving from? How do they enter the control and which way do they leave? The riders would have two sets of staircases to negotiate, one leading up and one back down. Neat rows of wooden stands had been provided ready for the riders to store their bikes while they went inside for their cards to be stamped. We picked out an area just outside the exit of the building for Chris to grab his food and bottles. We were pleased with ourselves for finding a nice bit of space, and laid all his kit out in a careful arrangement.

But our plan collapsed as soon as the riders arrived; it was chaos as more than a hundred riders descended on the control. The bike stands were ignored as bikes were shoved into the hands of their crew members, and everyone literally ran as quickly as their cleats would allow. Chris was alone to fight for himself having missed us, and we having missed him. Just in time Tarik heard Chris shouting for us; we scooped up all the kit and food and rushed to a panicked Chris. We loaded him up and got him underway, but not after he had wasted valuable minutes and causing him to sprint back to rejoin the front of the group.

We were shell-shocked. We hadn’t expected this chaos, this intensity. We knew from then on we’d have to up our game, pay closer attention – we couldn’t afford to let Chris down again or his confidence in us would be completely shattered.

Back in the car we sped off in the wrong direction in a panic, then struggled to regain our bearings. I urged Tarik to stop the car – we needed a quiet moment to get composed, to take some deep breaths. And then we were back on the road, this time pointing in the right direction.

Arriving in plenty of time at the next control in Fougeres, it was Chris’ turn to suffer the mayhem of P-B-P. Clearly riding strongly, he was visibly shaken after witnessing a multitude of crashes – and a couple at very close quarters. A car overtaking the peloton had crossed back across to the right side of the road too early – the trailer it was pulling clipped the front of the peloton with one rider taking the full brunt of the impact. I later learned that the rider was able to remount and fix-up his bike to finish the ride in a still impressive 59 hours. This despite being almost entirely unable to walk due to his injuries by the finish.

The official motorbike escort the leaders were given were more a liability than an assistance – one incident where two of their escorts became confused at which direction to take at an intersection caused eight riders to come down hard.

With a young wife and family back at home and a day job to return to the following week, Chris was questioning whether the risks were worth taking.

Each control produced a surge of adrenaline. After arriving and setting up our stall with bidons, foil wrapped food, and any spare kit ready should Chris request it, we would wait with heightening anticipation for the riders to arrive. During the night controls we used a green strobe light to signal our location to Chris, but generally we spotted him before he did us. It was generally my job to run to him and grab his bike and take it aside, swap out the bottles and fill up his small handlebar mounted bag with new provisions.

As the ride progressed, as the hours and kilometres ticked along at an astonishing rate, Chris required a little more assistance each time. Perhaps a couple more reassuring words, or helping him tug on knee and arm warmers, doing up the tricky zip on his high-viz jacket.

But just as it was taking its toll on Chris, so it was on us. Driving at night after so little sleep was becoming dangerous. We scrapped any thoughts of one driving while the other slept – we needed two pairs of eyes to stay alert and to keep the other awake. The strange hypnotic effect of driving along unlit roads, with only illuminated white lines as reference points made our tired eyes heavy and difficult to focus. Occasionally we grabbed naps of thirty minutes, often less, which was just enough to keep us functioning.

As morning drew closer the rain began to fall. We searched for places to get hot food for Chris, even hot water to make up some instant porridge, but with no success.

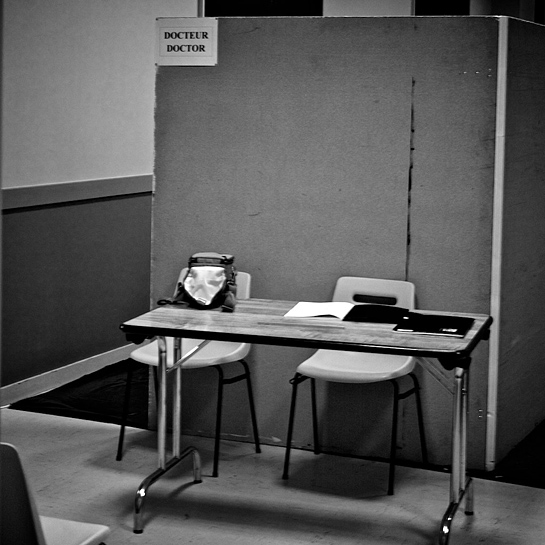

With the lead group so far ahead of the other riders, facilities at each control were not yet open. Large school canteens with industrial cooking equipment were unable to provide even the most basic of services. A simple kettle to boil water would have sufficed.

We hung around in deserted halls, rows and rows of empty chairs and tables. Just a few hours later, when we made the return trip from Brest, these same halls were filled with tired and hungry cyclists.

Arriving at Brest, and with it half of the 600km, it was becoming clearer who was actually left in the lead group. Only a fraction of the large group we witnessed careering through Montagne-au-Perche after 140km now remained.

Cries of “10 minutes! 10 minutes!” went up. It was clear most riders wanted to stop for longer at this control, wanting the chance to change kit, grab more than just a few hurried mouthfuls of food, and in some cases benefit from a brief leg massage. Chris however had been warned to be wary of such truces – agreements would be made, only for a few to slip away early and unnoticed to build a sly lead. To be safe Chris kept his stop as brief as possible, and was back on the road first. He later admitted he’d been persuaded to wait for the rest of the group only a few hundred metres further down the road. But it was better to be cautious.

From the exhausted faces around us at Brest it was becoming clearer that Chris was one of the strongest riders in the event. Only 600km to go.

As the second day turned to night, the rain returned, and with it crackling lightening that lit up the road ahead of us. At the Tinteniac control we witnessed riders still on their outward journeys seeking sanctuary in the dining hall. Some lay their heads on the tables, others curled up on the floor looking for sleep, some eager to push onwards donned their waterproofs and set off into the night.

A small group of traditional Bretagne dancers entertained the riders as they rolled in, but no one stopped to watch in the rain. The dancers paused occasionally as another flash of lightening ripped down.

Somewhere between Tinteniac and Fougeres, in the middle of the second night on the road, sleep-deprived, in the dark, Chris lead the group in the wrong direction. A twenty kilometres detour until they realised their mistake. We waited anxiously at Fougeres, and became increasingly concerned as a group of six riders arrived. Everyone was confused – these aren’t the leading riders. Or at least they weren’t.

The mistake cost Chris almost an hour in lost time, allowing a group of wily experienced competitors to jump ahead. Forty minutes was the deficit as Chris and the now second group on the road headed out towards Villaines-la-Juhel.

After being forced into giving into sleep, we were cutting our arrival to the next stop fine. But we were surprised to pull up to park near the control, only to watch Chris turn the corner and ride onwards away from us. We’d missed him! After a moments confusion we jumped into the car and chased after him – Tarik remembering that we were allowed on the riders’ route within a 5km radius of the controls.

It took us a while to catch Chris – he was motoring. Having dropped the rest of his group he was on a high. After handing over a couple of fresh bottles, we watched with a sense of awe as Chris literally sprinted away from us and in search of the four riders now less than thirty minutes ahead.

At the next control Chris had company in the form of a Belgian rider who had also jumped away from the second group. However it was clear that Chris had suffered some hard moments not long after sprinting away from us in Villaines-la-Juhel – waves of fatigue had forced him to grab a couple of moments rest in a roadside ditch. It was becoming less likely the leading group would be caught before Paris, despite a gradually shrinking deficit.

Back in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines to where we started almost fifty hours earlier to await the arrival of the fastest finishers at Paris-Brest-Paris 2011. A small crowd gathered; a few television cameras, a radio crew, friends and family, the odd rider who had abandoned and returned to the start.

As they appeared on the far side of a busy roundabout in this Parisian suburb I felt a lump of sadness that Chris wasn’t amongst them. He deserved this reception. But the wily veteran campaigners fully deserved their applause, the plaudits and press attention. The man to ride the course in the quickest time was Frenchman Tony Largeau in 44hrs 12mins. His companions – Marc Vedrinelle, André Ialenti and Christophe Bocquet – were a minute slower due to crossing the crowded start line slightly later.

Twenty minutes later, after the small crowd had dispersed and followed the victorious riders into the control building, Chris arrived. He shot us a resigned smile as he passed us – a look that encompassed all of the bad luck, and the good luck, he’d just experienced. It was an impressive ride, only made slightly less so by a simple error. His finishing time was 44hrs and 36min.

There is more to riding Paris-Brest-Paris than simple strength. Experience counts for a lot, as does having allies in the leading group. Chris fended for himself and impressed everyone with his ability to ride and ride, hour upon hour, with unwavering strength. At 33 Chris is still young for an endurance event such as this – he’s still yet to reach his peak, and if he returns in four years time, he’ll be equipped with the knowledge and skills to ride from Paris to Brest and back again even faster.

Footnote: A dark cloud hung over the event when it later emerged that American rider Thai Pham of the DC Randonneurs was killed on Monday night on the route near Médréac after drifting across the road into the path of an oncoming truck. Our thoughts go out to his friends and family.

Thanks to Tarik Djeddour who roped me into this adventure in the first place, and of course to Chris for not only being an incredibly strong rider, but a really nice guy too. When we messed up and knew we were letting Chris down he was quick to reassure us – we might not have felt like we were doing ‘an awesome job’, but he inspired us to do better.

You can see a video Tarik shot of Chris arriving at the finish here, and also a short chat Chris had with one of the leading four, Marc Vedrinelle. It’s clear Chris won their respect with his strong and selfless riding. More photos from our adventures are up on Flickr.

Reproduced from Damien Breen’s excellent blog – www.in-the-saddle.com