Over the coming weeks, we’ll be considering how to transfer the fitness developed to complete sportives into the speed needed to race successfully.

While at first glance a busy sportive and a road race may look very similar, the challenges posed by the two are often very different. Sportive riding generally requires good endurance to ride for four to six hours and rewards a steady, even pace.

By contrast, the characteristics of a racer are very different, with shorter distances (at least until you progress to elite level) and an emphasis very much on speed, riding in the ‘red zone’ and recovery.

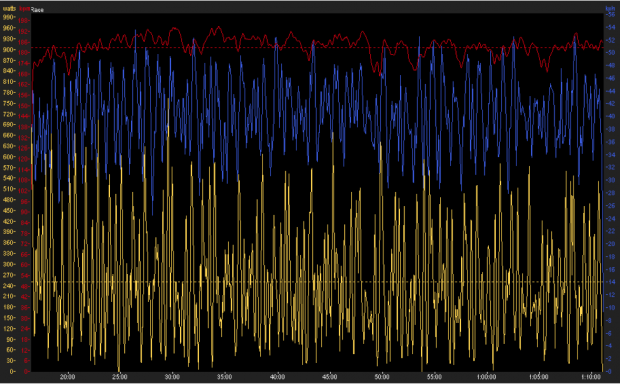

A well-trodden path into racing, whether as a complete newbie or coming from a sportive background, is to try time trialling, then maybe a local race on a closed circuit and finally, once bunch skills and speed have been developed, to try a sanctioned road race on the public highway. As you will see from the graphs below showing the power output and heart rate response to these types of effort, the different disciplines each have unique characteristics, sometimes very different to each other.

Time trials

Time trials are characterised by an even, well-paced effort (when ridden properly) with minimal changes in pace to allow the best possible effort over the distance. While power peaks instantaneously to get up to speed then settles down to a steady effort, heart rate rises steadily to threshold pace which is sustained all the way to the line.

Criteriums and circuit races

Criteriums or circuit races often last for a similar length of time to a time trial but display a very different pattern. While the average intensity may be lower than a time trial, a graph of the effort made is typically characterised by large spikes in power interspersed with recovery periods (unless you win solo!).

Road races

Road races are generally much longer than time trials and criteriums, and also have a varied intensity, ranging from periods of intense effort where you may need to go as hard as possible to hang on to the group or force a breakaway to periods of relative inactivity. The terrain often plays a big role here. As with sportives, you may encounter long climbs where the effort is steadier (like a time trial) but the key moments almost always involve going deep into the ‘red’.

Over the next few weeks, we will examine each discipline in greater detail, with tips on how to train specifically for each event. For now, however, we will focus on how to train for one of the key differences between sportives and road/criterium races, which is the sheer speed of the races and how to cope with the changes of pace required.

Training for speed and changes of pace

While the average intensity of a road race may fall into the ‘tempo’ training zone that you could maintain comfortably for several hours given the correct fuelling, the key to staying in the bunch and eventually winning races is speed.

You have the endurance and probably good threshold power from your sportive training, so first we will concentrate on developing your anaerobic capacity and top-end speed. This aspect of fitness is developed with maximal efforts lasting between 30 seconds and two minutes, with long recovery periods in between. At the shorter end of these intervals, go all out and hang on to the end of the 30-second effort.

A well-trodden path into racing is time trialling, then perhaps a circuit race, and finally a sanctioned road race on the public highway

In contrast, for one to two-minute efforts, it is easy to overcook things and ‘blow up’, so a degree of pacing is needed. Aim to work up to intervals of five to six minutes with at least five minutes of recovery in between to develop pure speed and maintain the quality of each interval.

A turbo trainer is a great tool here to allow you to go all out without needing to worry about your surroundings (watch that parked car!) or for more specificity find a short, steep climb to use: this will make sure you keep the effort up all the way to the end and allow you to practice gear selection for this type of effort in races.

Being able to do a one-off maximal effort is a great weapon in your arsenal and some people will be naturally gifted in this area. However, unless you can stay with the bunch, this will be useless, so you will also need to develop the ability to change pace and recover while still riding hard. As the average intensity of a road race will be in the tempo zone (easier than a time trial effort but still above your typical endurance or group ride) we will use that as a starting point.

Try riding at this intensity for 20 to 30 minutes, but within this, throw in a harder effort every three to five minutes. Jump hard as if you are responding to an attack, and ride hard for 30 seconds to one-minute before going straight back to your tempo intensity until the next hard effort. This will help you to respond to attacks and even attack in a road race but, on some technical courses especially, even more frequent maximal efforts are required to sprint out of each corner and respond to repeated attacks.

Repetition can quickly drain your energy and even leave you struggling “out the back”. To train this aspect of fitness, we need to replicate these demands in training. Again, the turbo trainer is your friend here, to allow you to keep on going with the maximal efforts without keeling over. As the aim here is to go hard and recover, the overall volume is once again low.

Top-end speed is developed with maximal efforts lasting between 30 seconds and two minutes, with long recovery periods in between

Start off with just 10 minutes of work, alternating with 20-second efforts at not quite a full-on sprint (choose a low gear and spin a high cadence for the ‘twenties’) with 40-seconds off, or very easy pedalling. If you’re doing this right you should be begging for a rest by the end of the 10-minute period. Build this up as your fitness progresses by alternating 30 seconds ‘on’ and 30 seconds ‘off’ and then switching the original workout so you are doing 40 seconds ‘on’ and just 20 seconds recovery.

All these sessions should fit into a balanced training programme rather than as the sole components to develop all aspects of your fitness. For more guidance a coach is an invaluable resource, whether for advice on where to fit these sessions in, or to provide tactical and technical guidance to give you the skills needed for bunched racing and detailed training prescription to get the most out of your precious training time.