In just shy of nine days, British rider James Hayden rode 3,650km across Europe, spending the equivalent of six days, 23 hours in the saddle to win the fifth Transcontinental race – a gruelling, sleep-deprived feat of endurance, battling extreme heat, fatigue and nomadic stamina.

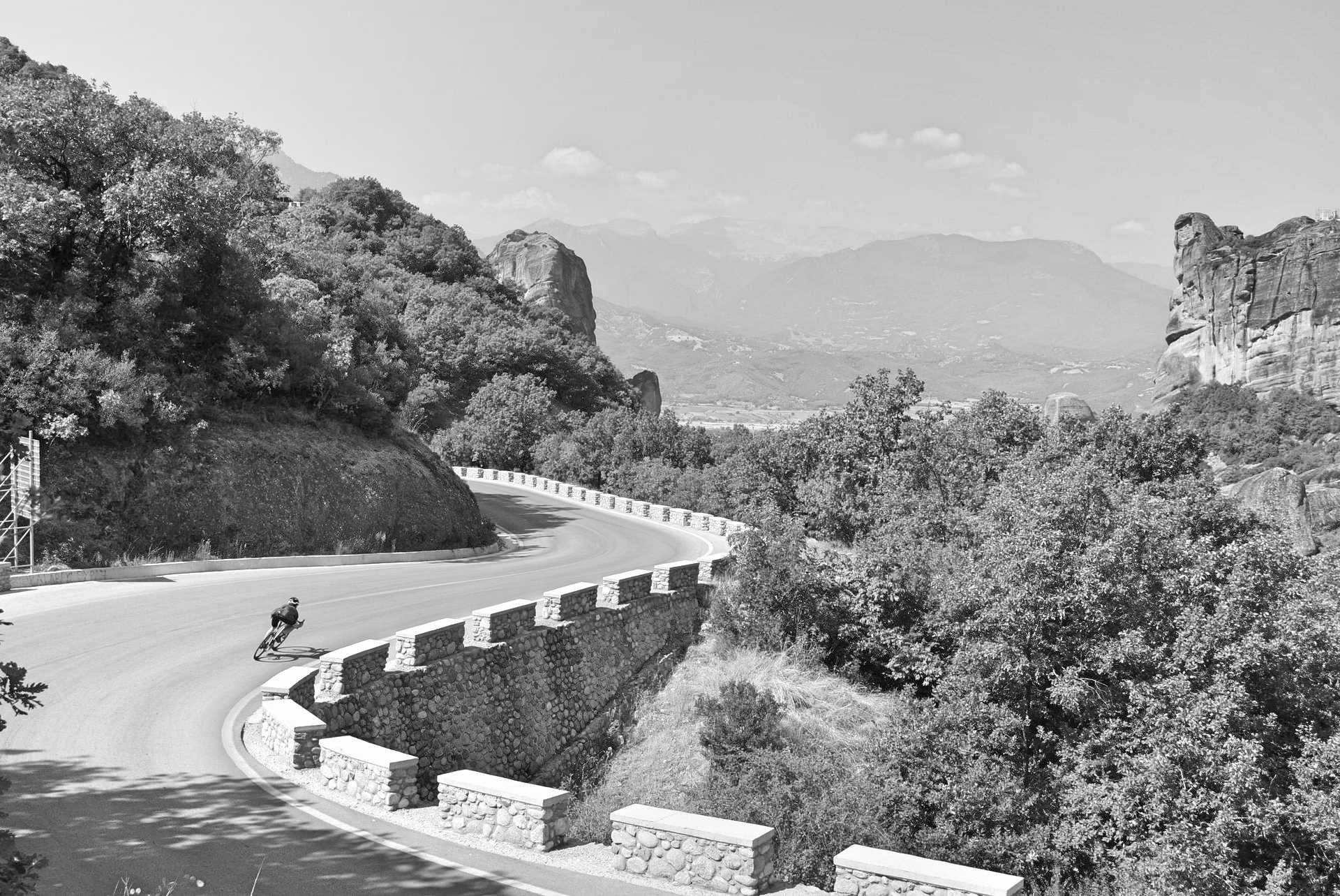

The brainchild of the late Mike Hall, this year’s Transcontinental race took place from Flanders, Belgium, to Meteora, Greece, and was the first to be run since the Yorkshireman’s death during the inaugural IndyPac race in March.

Mike’s friends and family stepped in to organise the event, with Hayden admitting pre-race it would be a ‘bittersweet experience’ but promising to honour Hall. TCR is a self-supported race with no set course, though riders must visit four ‘controls’ en-route, this year in Germany (Schloss Lichtenstein, Swabia), Italy (Monte Grappa, Treviso), Slovakia (High Tatras) and Romania (Transfăgărășan mountain pass), ensuring a variety of meandering routes through some of Europe’s toughest terrain.

Unfortunately more tragedy struck during the event, when a Dutch competitor, Frank Simons, died after a hit-and-run collision with a car, just 82km into his ride. But after organisers opted to continue with the event, in accordance with Simons’ wife’s wishes, it was Hayden, on his Fairlight Strael, who claimed victory in Meteora.

For the first installment of our new Q&A series, Ten minutes with…, we caught up with Hayden to find out just what it takes to win Transcontinental.